Sudano-Sahelian Architecture

Sudano-Sahelian architecture refers to a range of similar indigenous architectural styles common to the African peoples of the Sahel and Sudanian grassland (geographical) regions of West Africa, south of the Sahara, but north of the fertile forest regions of the coast.

This style is characterized by the use of mudbricks and adobe plaster, with large wooden-log support beams that jut out from the wall face for large buildings such as mosques or palaces. These beams also act as scaffolding for reworking, which is done at regular intervals, and involves the local community. The earliest examples of Sudano-Sahelian style probably come from Jenné-Jeno around 250 BC, where the first evidence of permanent mudbrick architecture in the region is found.[1]

Difference between Savannah and Sahelian styles

The earthen architecture in the Sahel zone region is noticeably different from the building style in the neighboring savannah. The "old Sudanese" cultivators of the savannah built their compounds out of several cone-roofed houses. This was primarily an urban building style, associated with centres of trade and wealth, characterised by cubic buildings with terraced roofs comprise the typical style.

They lend a characteristic appearance to the close-built villages and cities. Large buildings such as mosques, representative residential and youth houses stand out in the distance. They are landmarks in a flat landscape that point to a complex society of farmers, craftsmen and merchants with a religious and political upper class.

With the expansion of Sahelian kingdoms south to the rural areas in the savannas (inhabited by culturally or ethnically similar groups to those in the Sahel), the Sudano-Sahelian style was reserved for mosques, palaces, the houses of nobility or townsfolk (as is evident in the Gur-Voltaic style), whereas among commonfolk, there was a mix between either typically distinct Sudano-Sahelian styles for wealthier families, and older African roundhut styles for rural villages and family compounds.

Substyles

The Sudano-Sahelian architectural style itself can be broken down into four smaller sub-styles that are typical of different ethnic groups in the region. The examples used here illustrate the construction of mosques as well as palaces, as the architectural style is concentrated around inland Muslim populations.

As with the people, many of these styles cross-pollinate and produce buildings with shared features. Any one of these styles is not exclusive to one particular modern countries borders, but are linked to the ethnicity of its builders or surrounding populations. For example, a Malian migrant community in traditionally Gur area may build in the style characteristic of their ancestral homeland, while neighbouring Gur buildings are built in the local style. These styles include:

-

Malian – of the various Manden groups of southern and central Mali. The architecture of Mali comprises adobe buildings characterized by:

- The Great Mosque of Djenne

- The city of Timbuktu has many adobe and mud brick buildings, collectively known as the University of Timbuktu, which were the centres of learning in medieval Mali and produced some of the most famous works in Africa such as the Timbuktu Manuscripts. The most famous of these buildings include the masajids (mosques) of:

- Fortress style – predominantly used by the Zarma peoples of northern Nigeria and Niger, Hausa-Fulani, Tuareg and Arab mixed communities in Agadez, the Kanuri people of Lake Chad, and Songhai of northeastern Mali. Military aspect to construction of high protective compound walls built around a central courtyard. Minaret is the only structure with support beams showing. Characterized by the Sankore Mosque of Timbuktu, the Tomb of Askia in Gao Mali, and the Agadez Mosque of northern Niger.

-

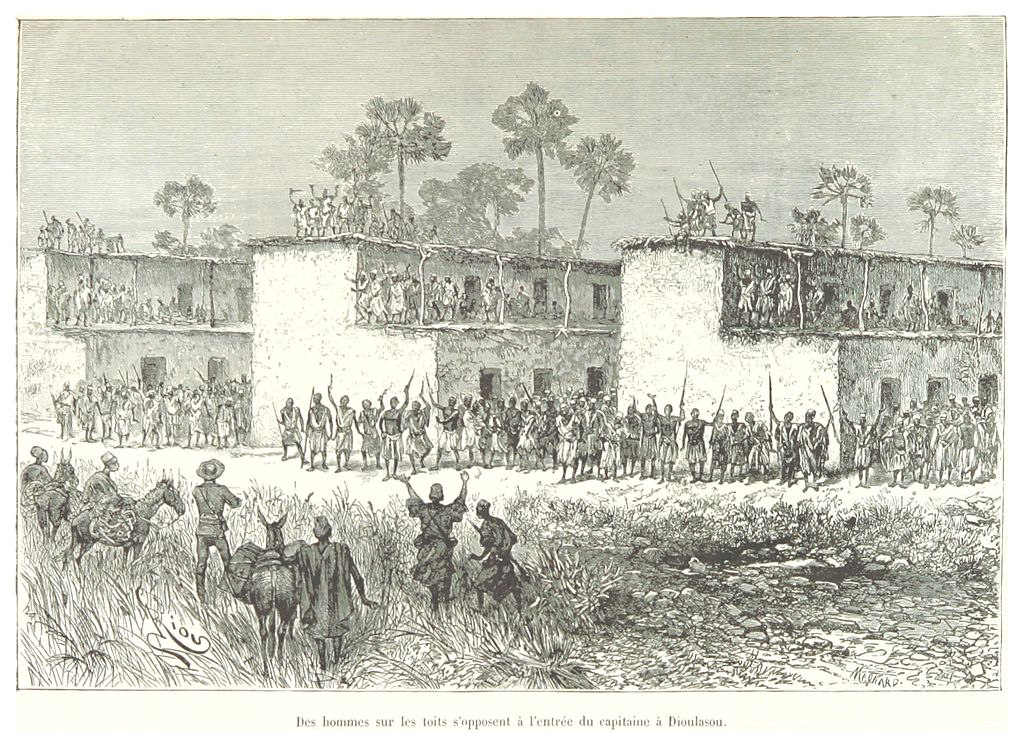

Tubali – The characteristic Hausa architectural style predominant in North and Northwestern Nigeria, Niger, Eastern Burkina Faso, Northern Benin, and Hausa-predominant zango districts and neighbourhoods throughout West Africa.

Hausa buildings are characterized by the use of dry mud bricks in cubic structures, multi-storied buildings for the social elite, the use of parapets related to their military/fortress building past, and traditional white stucco and plaster for house fronts. At times the facades may be decorated with various abstract relief designs, sometimes painted in vivid colours to convey information about the occupant.

Examples include:- Yamma Mosque

-

The old town of Zinder

-

The Hausa quarter of Agadez, Niger

-

The Gidan Rumfa of Kano

- Volta basin – of the Gur and Manden groups of Burkina Faso, northern Ghana and northern Cote d'Ivoire. The most conservative of the three styles. A single courtyard, characterized by high white and black painted walls, inward curved turrets supporting an exterior wall, and a larger turret nearer the center. Characterized by the:

Sudano-Sahelian Styles by Region

Tichitt

Dhar Tichitt, Tichitt Walata, and Dhar Nema are the oldest surviving collection of settlements in West Africa and the oldest of all stone-base settlement south of the Sahara. They were built by the Soninke people and are thought to be the precursors of the Ghana empire.

The region was settled by agropastoral people around 2000–300 BCE, which makes it almost 1000 years older than previously thought. One finds well-laid-out streets and fortified compounds, all made out of skilled stone masonry. In all, there were 500 settlements.

In addition to herding livestock, its inhabitants fished and grew millet.

The Dhar Tichitt site had become a complex culture by 3600 BP and had architectural and material culture elements that seemed to match the site at Koumbi Saleh. Koumbi Saleh is the site of a ruined medieval town in south east Mauritania that may have been the capital of the Ghana Empire.

Kumbi Saleh

At Kumbi Saleh, locals lived in dome-shaped dwellings in the king's section of the city, surrounded by a great enclosure. Traders lived in stone houses in a section which possessed 12 beautiful mosques (as described by al-Bakri), one of which was for Friday prayer.[16] The king is said to have owned several mansions, one of which was sixty-six feet long and forty-two feet wide, contained seven rooms, was two stories high, and had a staircase, with paintings on the walls and chambers filled with sculpture.Sahelian architecture initially grew from the two cities of Djenné and Timbuktu. The Sankore Mosque, constructed from mud on timber, was similar in style to the Great Mosque of Djenné.

Ashanti architecture from Ghana is perhaps best known from the reconstruction at Kumasi. Its key features are courtyard-based buildings, and walls with striking reliefs in brightly painted mud plaster. An example of a shrine can be seen at Bawjiase in Ghana. Four rectangular rooms, constructed from wattle and daub, lie around a courtyard. Animal designs mark the walls, and palm leaves cut to a tiered shape provide the roof.

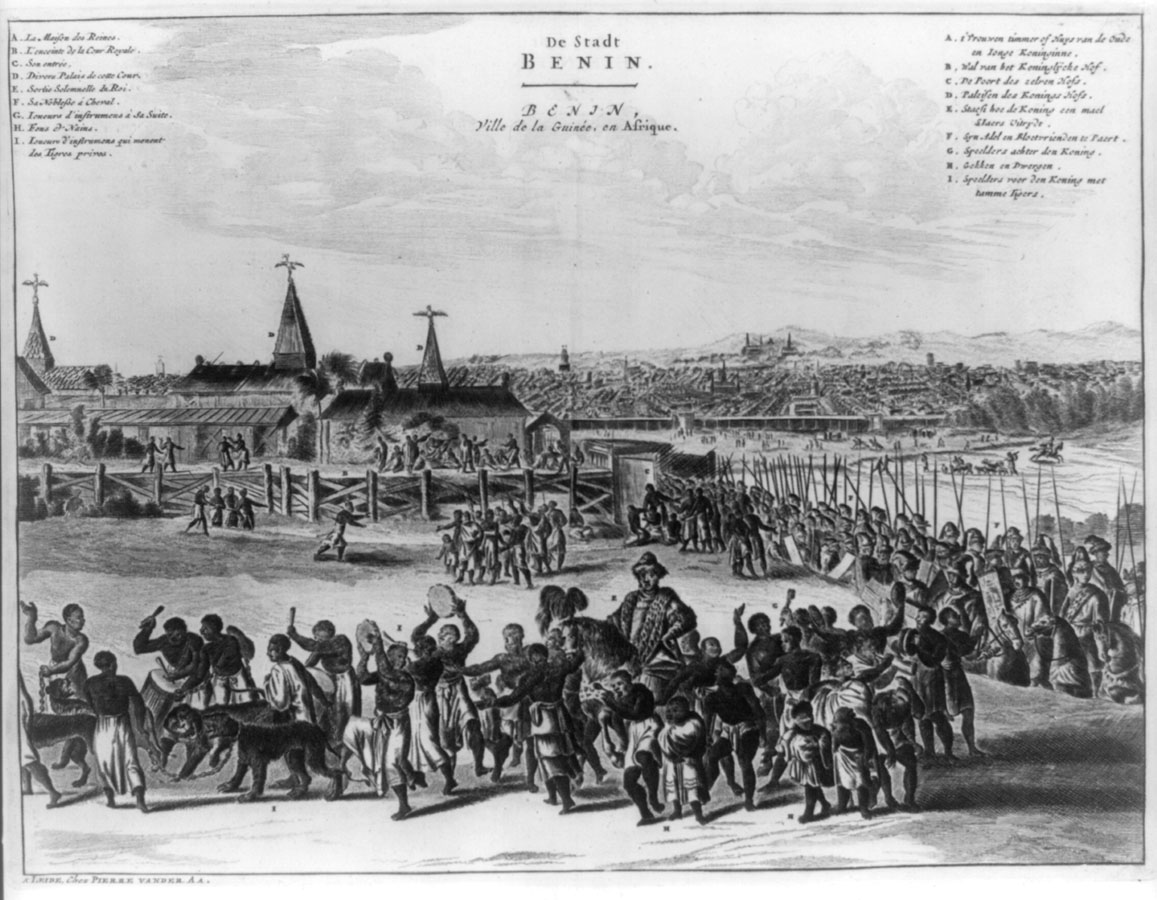

Benin City

Benin City, originally known as Edo, was once the capital of The Benin Empire. The rise of kingdoms in the West African coastal region produced architecture which drew on indigenous traditions, utilizing wood. Benin City was a large complex of homes in coursed mud, with hipped roofs of shingles or palm leaves. The palace contained a sequence of ceremonial rooms and was decorated with brass plaques.The city was made of hundreds of interlocked cities and villages laid out to form perfect fractals. The main streets had underground drainage made of a sunken impluvium with an outlet to carry away storm water. Metal lamps fuelled by palm oil provided street lighting at night.

The city was enclosed by massive walls made from earthworks longer than the Great Wall of China. The walls were built of a ditch and dike structure; the ditch dug to form an inner moat with the excavated earth used to form the exterior rampart.

The Benin Walls were ravaged by the British in 1897 during what has come to be called the Punitive expedition. Scattered pieces of the structure remain in Edo, with the vast majority of them being used by the locals for building purposes. What remains of the wall itself continues to be torn down for real estate developments.[2]

Fred Pearce wrote in New Scientist:

They extend for some 16,000 km in all, in a mosaic of more than 500 interconnected settlement boundaries. They cover 2,510 sq. miles (6,500 square kilometres) and were all dug by the Edo people. In all, they are four times longer than the Great Wall of China, and consumed a hundred times more material than the Great Pyramid of Cheops. They took an estimated 150 million hours of digging to construct, and are perhaps the largest single archaeological phenomenon on the planet.[3]

Ethnomathematician Ron Eglash has discussed the planned layout of the city using fractals as the basis, not only in the city itself and the villages but even in the rooms of houses. He commented that "When Europeans first came to Africa, they considered the architecture very disorganised and thus primitive. It never occurred to them that the Africans might have been using a form of mathematics that they hadn’t even discovered yet.[4]

Sungbo's Eredo

Sungbo's Eredo is a system of defensive walls and ditches that is located to the southwest of the Yoruba town of Ijebu Ode in Ogun State, southwest Nigeria (6.78700°N 3.87488°E). It was built in honour of the Ijebu noblewoman Oloye Bilikisu Sungbo.

The total length of the fortifications is more than 160 kilometres (99 mi). The fortifications consist of a ditch with unusually smooth walls and a bank in the inner side of ditch. The height difference between the bottom of the ditch and the upper rim of the bank on the inner side can reach 20 metres (66 ft). Works have been performed in laterite, a typical African soil consisting of clay and iron oxides. The ditch forms an uneven ring around the area of the ancient Ijebu Kingdom, an area approximately 40 kilometres (25 mi) wide in north-south, with the walls flanked by trees and other vegetation, turning the ditch into a green tunnel.

This page uses materials from Wikipedia available in the references. It is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

References