Somali

Somali architecture is the engineering and designing of multiple different construction types such as stone cities, castles, citadels, fortresses, mosques, temples, aqueducts, lighthouses, towers and tombs during the ancient, medieval and early modern periods in Somalia and other regions inhabited by Somalis, as well as the fusion of Somalo-Islamic architecture with Western designs in contemporary times.

Ancient

Walled settlements, temples and tombs

Encyclopedias from ca. 1900 note that ancient tombs, pyramidal structures, ruined towns, ancient inscriptions, and stone walls found in Somalia, such as the Wargaade Wall, are evidence of an old civilization in the Somali peninsula that predates Islam. [10]

In an 1878 report to the Royal Geographical Society of Great Britain, Johann Maria Hildebrandt noted upon visiting the area that " we know from ancient authors that these districts, at present so desert, were formerly populous and civilised[...] I also discovered ancient ruins and rock-inscriptions both in pictures and characters[...] These have hitherto not been deciphered."[12]

Archaeological sites where ancient inscriptions have been found on cave paintings include Godka Xararka in Las Anod District, Qubiyaaley in Las Anod District, Hilayo in Las Khoray District, Karin Heeggane in Las Khoray District, and Dhalanle in Las Khoray District.[13]

According to the Ministry of Information and National Guidance of Somalia, inscriptions featuring the ancient script are particularly noteworthy on the various old Taalo Tiiriyaad structures. These are enormous stone mounds found especially in northeastern Somalia. Among the main sites where these Taalo are located are: Xabaalo Ambiyad in Alula District, Baar Madhere in Beledweyne District, and Harti Yimid in Las Anod District. [13]

Besides stone monuments, cave paintings and granite rocks, the ancient script has also been found on old coins in various parts of Somalia.[13]

Wargaade Wall

Wargaade Wall is an ancient stone construction in Wargaade, Somalia. It enclosed a large historic settlement in the region.

Graves and unglazed sherds of pottery dating from antiquity have been found during excavations in the area. The Wall's building material consists of rubble set in mud mortar. The high wall measures 230 m × 210 m (750 ft × 690 ft). After the settlement was abandoned during the Islamic era, the population of Wargaade began using the wall as a source for building material, which contributed to its current eroded state.[9]

Ras Hafun

Ras Hafun is home to numerous ancient structures and ruins. The peninsula is believed to be the location of the old trade emporium of Opone. The latter is mentioned in the anonymous Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, written in the first century CE. Opone is described therein as a busy port city, strategically located on the trade route that spanned the length of the Indian Ocean's rim.

A later expedition in Hafun, led by an archaeological team with the University of Michigan, excavated Ancient Egyptian, Roman and Persian Gulf pottery. In the 1980s, the British Institute in Eastern Africa also recovered pre-Islamic Partho-Sassanid ceramics from the peninsula, which were dated to the first century BCE and the second through fifth centuries CE.

Archaeological excavations at the western Hafun site have yielded ceramics from ancient kingdoms in the Nile Valley, Near East, Persia and Mesopotamia, as well as some sherds of possible derivation from the Indian subcontinent. Among this ware is a late Ptolemaic lamp fragment, Parthian glazed sherds, and Hellenistic lagynos wares. Smith and Wright have dated the finds to sometime between the 1st century BCE and the early first century CE. Additionally, some ceramics affiliated with green glazed ware from Sohar on the Omani littoral have also been found in the area. These pieces have been dated to between the 1st century BC and the 5th century BCE.

Hafun is also home to an ancient necropolis. Similar historical structured areas exist in various other parts of the country.

Port Dunford

Port Dunford in the southern Lower Juba province contains a number of ancient ruins, including several pillar tombs. Prior to its collapse, one these structures' pillars stood 11 meters high from the ground, making it the tallest tower of its kind in the wider region.[15] The site is believed to correspond with the ancient emporium of Nikon, which is described in the 1st century CE Greco-Roman travelogue the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.[16] In the southern town of Hannassa, ruins of houses with archways and courtyards have been found along with other pillar tombs, including a rare octagonal tomb.[17] Additionally, various pillar tombs exist in the southeastern Marca area. Local tradition holds that these were built in the 16th century, when the Ajuran Sultanate's naa'ibs governed the district.[18]Taalo - burial cairns

Some of the oldest known structures (many of which have yet to be properly explored) in the territory of modern-day Somalia consist of burial cairns (taalo).[1] Northern Somalia in particular is home to numerous such archaeological structures, with many similar edifices found at:- Haylan - An old settlement, Haylan is the site of numerous ancient ruins and buildings, many of obscure origins.

- Qa’ableh - is believed to harbor the tombs of former kings from early periods of Somali history, as evidenced by the many ancient burial structures and cairns (taalo) that are found here.2

- Qombo'ul - is a historical town in the eastern Sanaag region of Somalia.

- El Ayo - is one of a series of ancient settlements in northern Somalia. About one mile from the town are the ruins of an old city, which are held to have belonged to an earlier civilization.

- Heis- is a coastal town in the northern Sanaag province of Somaliland. A large collection of cairns of various types lie near the city.[4] Excavations here have yielded pottery and sherds of Roman glassware from a time between the 1st and 5th centuries.[2][3] Among these artefacts is high-quality millefiori glass.[4] Dated to 0-40 CE, it features red flower disks superimposed on a green background.[7] Additionally, an ancient fragment of a footed bowl was discovered in the surrounding area. The sherd is believed to have been made in Aswan (300-500 CE) or Lower Nubia (500-600 CE), suggesting early trading ties with kingdoms in the Nile Valley.[8]

Earthwork - Near Bosaso, at the end of the Baladi valley, lies a 2 km to 3 km long earthwork.[1][14] Local tradition recounts that the massive embankment marks the grave of a community matriarch. It is the largest such structure in the wider Horn region.[14]

Sheekh - is a town in the northwestern Sahil province of Somaliland. Sheekh is noted for its numerous historical structures. Ancient temples found in the town are reportedly similar to those in the Deccan Plateau in South Asia.

Stelae - Surveys by A.T. Curle in 1934 on several ruined cities recovered various artefacts, such as pottery and coins, which point to a medieval period of activity at the tail end of the Adal Sultanate's reign.[19] Among these settlements, Aw Barkhadle is surrounded by a number of ancient stelae.[20] Burial sites near Burao likewise feature old stelae.[21]

Medieval

The introduction of Islam in the early medieval era of Somalia's history brought Islamic architectural influences from the Arabian Peninsula and Persia. This stimulated a shift from drystone and other related materials in construction to coral stone, sundried bricks, and the widespread use of limestone in Somali architecture. Many of the new architectural designs such as mosques were built on the ruins of older structures, a practice that would continue over and over again throughout the following centuries.[22]

Stone cities

The lucrative commercial networks of successive medieval Somali kingdoms and city-states such as the Adal Sultanate, Sultanate of Mogadishu, Ajuran Sultanate, and the Sultanate of the Geledi saw the establishment of several dozen stone cities in the interior of Somalia as well as the coastal regions. Ibn Battuta visiting Mogadishu in the early 14th century called it a town endless in size [23] and Vasco Da Gama who passed by Mogadishu in the 15th century noted that it was a large city with houses of four or five storeys high and big palaces in its centre[24]

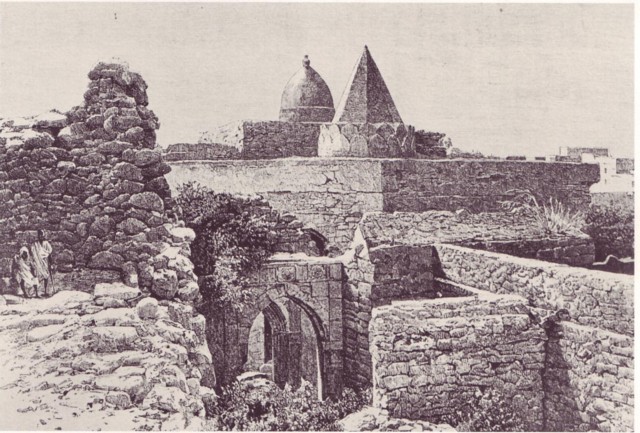

Ruins of the Sultanate of Adal in Zeila.

- Whitewashed coral stone city of Merca.

Somali merchants were an integral part of a long distance caravan trade network connecting major Somali cities, such as Mogadishu, Merca, Zeila, Berbera, Bulhar and Barawa, with other business centers in the Horn of Africa. The numerous ruined and abandoned towns throughout the interior of Somalia can be explained as the remains of a once booming inland trade dating back to the medieval period.[25]

Goan Bogame, situated in the Las Anod District, contains the ruins of a large ancient city with around two hundred buildings. The structures were built in an architectural style similar to that of the edifices in Mogadishu's old Hamar Weine and Shangani districts.[1][14]

Castles and fortresses

Throughout the medieval era, castles and fortresses known as Qalcads were built by Somali Sultans for protection against both foreign and domestic threats. The major medieval Somali power engaging in castle building was the Ajuran Sultanate, and many of the hundreds of ruined fortifications dotting the landscapes of Somalia today are attributed to Ajuran engineers.[26]

19th century Martello fort in Berbera constructed by Haji Sharmarke Ali Saleh.

- Ruins of the Majeerteen Sultanate King Osman Mahamuud's castle in Bargal, built in 1878.

In the year 1845, Haji Sharmarke Ali Saleh seized Berbera, constructed four Martello style forts within the vicinity of the town, and garrisoned each fort with thirty matchlock men.[27]

The Dervish State in the late 19th century and early 20th century was another prolific fortress building power in the Somali Peninsula. In 1913, after the British withdrawal to the coast, the permanent capital and headquarters of the Dervishes was constructed at Taleh, a large walled town with fourteen fortresses. The main fortress, Silsilat, included a walled garden and a guard house. It became the residence of Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, his wives, family, prominent Somali military leaders, and also hosted several Turkish, Yemeni and German dignitaries, architects, masons and arms manufacturers.[28] Several dozen other fortresses were built in Illig, Eyl, Shimbiris and other parts of the Horn of Africa.

- Aerial view of Mohammed Abdullah Hassan's main fort in Taleh, the capital of his Dervish State.

Citadels and city walls

City walls were established around the coastal cities of Merca, Barawa and Mogadishu to defend the cities against powers such as the Portuguese Empire. During the Adal Age, many of the inland cities such as Amud and Abasa in the northern part of Somalia were built on hills high above sea level with large defensive stone walls enclosing them. The Bardera militants during their struggle with the Geledi Sultanate had their main headquarters in the walled city of Bardera that was reinforced by a large fortress overseeing the Jubba river. In the early 19th century the citadel of Bardera was sacked by Sultan Yusuf Mahamud Ibrahim and the city became a ghost town.

Somali city walls also acted as a barrier against the proliferation of arms usually carried by the Somali and Horn African nomads entering the cities with their caravan trains. They had to leave behind their weapons at the city gate before they could enter the markets with their goods and trade with the urban Somalis, Middle Easterners and Asian merchants.[29]

- The Citadel of Gondershe.

Mosques and shrines

Concordant with the ancient presence of Islam in the Horn of Africa region, mosques in Somalia are some of the oldest on the entire continent. One architectural feature that made Somali mosques distinct from other mosques in Africa were minarets.

For centuries, Arba'a Rukun (1269), the Friday mosque of Merca (1609) and Fakr ad-Din (1269) were, in fact, the only mosques in East Africa to have minarets.[25] Arba Rukun's massive round coral tower of about 13 and a half meters high and over four meters in diameter at its base has a doorway that is narrow and surrounded by a multiple ordered recessed arch, which may be the first example of the recessed arch that was to become a prototype for the local mihrab style.

Constructed by and named after the first Sultan of the Mogadishu Sultanate, the Fakr-ad Din mosque dates back to the 1269. Built with marble and coral stone on a compact rectangular plan, it features a domed mihrab central azis. Glazed tiles were also used in the decoration of the mihrab, one of which bears a dated inscription. In addition, the masjid is characterized by a system of composite beams, alongside two main columns. This well-planned, sophisticated design is not replicated in mosques further south outside the Horn region.[30]

17th-century mosque in Hafun, Somalia.

- 13th century Fakr ad-Din mosque built by Fakr ad-Din, the first Sultan of the Mogadishu Sultanate.

The 13th century Al Gami University consisted of a rectangular base with a large cylindrical tower architecturally unique in the Islamic world.

Shrines erected to house and honor Somali patriarchs and forefathers evolved from ancient Somali burial customs. Such tombs, which are predominantly found in northern Somalia (the suggested point of origin of the Somalia's majority Somali ethnic group), feature structures mainly consisting of domes and square plans. [31] In southern Somalia, the preferred medieval shrine architecture was the pillar tomb-style.

A number of ancient burial sites dated from the pre-Islamic period sit atop the peak of Buur Heybe, a granitic inselberg in the southern Doi belt. They serve as a center of annual pilgrimage (siyaro). These burial sites on the mountain's summit were later made into Muslim holy sites in the ensuing Islamic period, including the Owol Qaasing (derived from the Arabic "Abul Qaasim", one of the names of Prophet Muhammad) and Sheikh Abdulqadir al-Jilaani (named for the founder of the Qadiriyya order).[32]

This page uses materials from Wikipedia available in the references. It is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

References