Nubian Kingdoms

A-Group culture

The earliest archeological finds of Nubia origin come from cemeteries linked to an ancient civilization that flourished between the First and Second Cataracts of the Nile in Nubia called the A-Group culture (c. 3800 BC to c. 3100 BC):

The A-Group population practiced flood plain agriculture, animal husbandry, and conducted trade. Unfortunately, the Group's settlements cannot be traced in precision because of two reasons. First, their houses were built of perishable materials, such as unbaked-mud. Second, the Group's settlements were established very close to the Nile river where seasonal floods would have destroyed them long time ago. Therefore, most of what we know about the A-Group culture comes from the cemeteries located few miles away from the Nile Valley.

The material culture uncovered from the burials suggests a complex culture with a hierarchical structure. Excavations in cemeteries, in Sudan's northern border area, provided a good insight on the social complexity of the Group. The sizes of the graves there indicate the social status of the deceased. The larger the grave the richer was the deceased, and the smaller the poorer was the deceased. [2]

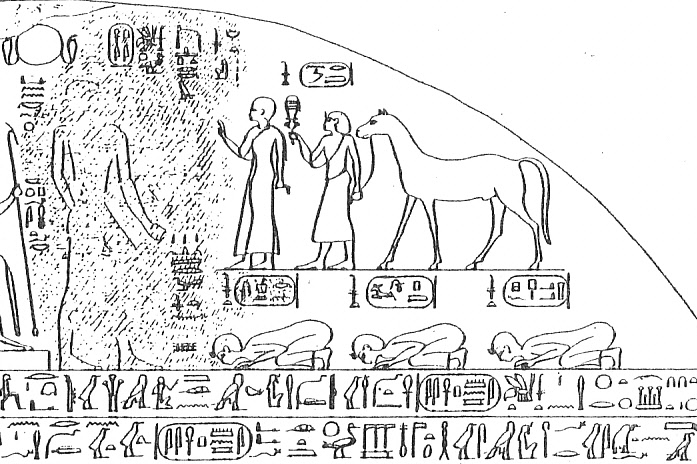

The A-Group culture represents the earliest known phase of state formation and Kingship on the Nile. Excavations at Qustul (Lower Nubia) have indicated that the Nubians may have founded the earliest Monarchy in the Nile Valley, dated between 3800 BC to 3400 BC, older than the Scorpion King who was the earliest known Egyptian ruler. [1] The artifacts were discovered by Keith C. Seele, a professor at the University of Chicago. Of particular intrest was a an incense burner, which was adorned with Ancient Egyptian royal iconography [1]:

On the incense burner, which was broken and had to be pieced together, was a depiction of a palace facade, a crowned king sitting on a throne in a boat, a royal standard before the king and, hovering above the king, the falcon god Horus. Most of the images are ones commonly associated with kingship in later Egyptian traditions.

The portion of the incense burner bearing the body of the king is missing but, Dr. Williams said, scholars are agreed that the presence of the crown — in a form well known from dynastic Egypt — and the god Horns are irrefutable evidence that the complete image was that of a king.’

The majestic figure on the incense burner, Dr. Williams said, is the earliest known representation ‘of a king in the Nile Valley. His name is unknown, but he is believed to have lived approximately three generations of kings before the time of Scorpion, the earliest known Egyptian ruler. Scorpion was one of three kings said to have ruled Egypt before the start of what is called the first dynasty around 3050 B.C. [1]

Although the incense burner was adorned with Ancient Egyptian royal iconography, it's design was distinctively Nubian:

This incense burner is distinctively Nubian in form. Carved in the technique of Nubian rock art, it is decorated on the rim with typical Nubian designs. It was found in the tomb of a Nubian ruler at Qustul and incorporates images associated with Egyptian pharaohs: a procession of sacred boats, the White Crown of Upper Egypt, a falcon deity, and the palace facade called a serekh. It appears to represent a ritual that involved a royal procession by boat to a palace.

The scenes depicted on the Qustul Incense Burner have excited considerable interest and discussion - why would seemingly Egyptian symbols have been used in Nubia?

One interpretation is that Nubian A-Group rulers and early Egyptian pharaohs used related royal symbols. Similarities in rock art of A-Group Nubia and Upper Egypt support this position.

Another view suggests that the decoration was carved by Nubians in imitation of Egyptian art and rituals. In this perspective, A-Group Nubian rulers would have emulated the symbols of Egyptian pharaohs, whose prestige and power were evident.[2]

The A-Group culture came to an end around 3100 BC, when it was destroyed by the First Dynasty rulers of Egypt.

C-Group culture

The A-Group culture was followed later by the C-Group culture (2200-1500 BCE). Settlements consisted of round structures with stone floors. The C-Group culture had roots in sub-saharan African culture:

Small circular houses with stone foundations, handmade ceramics with elaborate incised decoration, and graves covered with circular stone mounds are features that C-Group shared with earlier Nubian A-Group and Pre-Kerma cultures. But the importance of cattle in the C-Group, shown in its burial stelae, pottery, figurines, and rock drawings, also links it firmly to the African cattle cultures that began in the Neolithic and then spread across sub-Saharan Africa.[5]

The C-Group culture also had deep ties with Egypt:

C-Group cemeteries are found as far north as Hierakonpolis in southern Egypt, and Egyptians traveled and traded in Nubia. Many Nubians were soldiers in Egyptian armies. Nubian troops featured prominently in warfare during Egypt’s First Intermediate Period (about 2100 BC), a time of civil unrest. Egyptian traders and returning Nubian soldiers brought Egyptian goods including amulets, pots, and valuable gold and silver necklaces to Nubia. Though first ruled by Egypt and then by Kerma, C-Group culture retained its own distinctive customs for centuries. Later, C-Group traditions became less visible in archaeological remains as Nubians adopted Egyptian styles during the Egyptian New Kingdom occupation of Nubia (1550–1069 BC).[5]

The C-Group culture was related to the later Kerma Culture. Archeologists uncovered several ancient constructions dating back to the pre-Kerma period (4th millennium BC- 2600 BC).[3]

Kerma culture

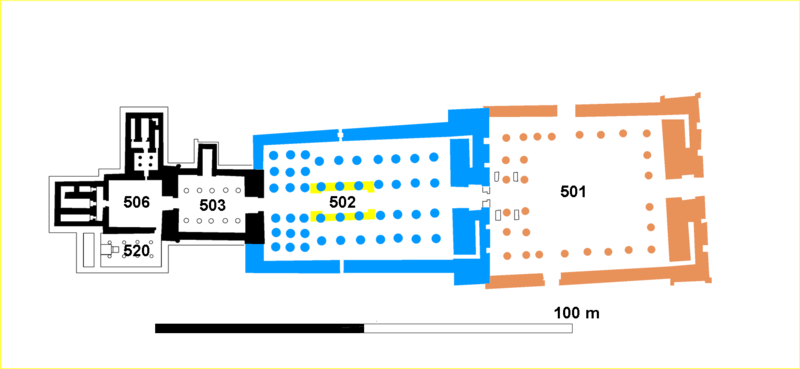

Kerma (also known as Dukki Gel) was the capital city of the Kerma culture in present-day Sudan. Kerma was settled around 2500 BCE. It was a walled city containing a religious building, large circular dwelling, a palace, bronze forges, and well laid out roads. Kerma was built around a large adobe temple known as the Deffufa, a mud brick temple where ceremonies were performed on top.[4]

Kerma has been excavated by a Swiss team for more than 30 years. The team has discovered the remains of temples, cemeteries and a city wall with bastions. Their discoveries reveal that the city was a center for trade with gold, ivory and cattle among other commodities being traded by Kerma's inhabitants. The exact amount of territory that Kerma controlled is uncertain, but it appears to have encompassed part of what is now Sudan and southern Egypt.[9]

Between 1500-1085 BCE, Egyptian conquest and domination of Nubia was achieved. This conquest brought about the Napatan Phase of Nubian history.

Napata was founded by Egyptian pharaohThutmose III in the 15th century BC after his conquest of Nubia. The nearby Jebel Barkal was taken to mark the southern border of the New Kingdom of Egypt.

Twenty-fifth Dynasty

In 1075 BCE fragmentation of power in Egypt allowed the Nubians to regain autonomy. They founded the Kingdom of Kush, which was centered at Napata, and eventually conquered Egypt in 750 BC. They constitute the Twenty-fifth Dynasty in Manetho’s Aegyptiaca. The Twenty-fifth Dynasty ruled for a little more than one hundred years.

The 25th Dynasty's reunification of Lower Egypt, Upper Egypt, and Kush created the largest Egyptian empire since the New Kingdom and ushered in a renaissance restoring traditional Egyptian values, culture, art, and architecture.

...the 25th Dynasty "Negro" kings are now recognized as having sponsored an important renaissance of Egyptian art and culture; they developed an almost scholarly interest in ancient Egyptian traditions and language and have been called "the first Egyptologists." The empire over which they presided was greater in extent than any ever achieved in antiquity along the Nile Valley. Their kings were said never to have condemned prisoners to death; they forgave their enemies and allowed them to retain their offices; they also actually gave public credit for achievement in their inscriptions to individuals other than themselves. Such characteristics among other ancient monarchs of Egypt or the Near East are unheard of, and we can only assume these were native Nubian qualities.[6]

The Pharos of the 25th dynasty assimilated into society by reaffirming Ancient Egyptian religious traditions, temples, and artistic forms, while introducing some unique aspects of Kushite culture.

Piye, the first Pharaoh of the 25th dynasty, revived pyramid construction. He constructed the oldest known pyramid at the royal burial site of El-Kurru and expanded the Temple of Amun at Jebel Barkal.

Piye was certainly remembered not as a conquering overlord, but as a just and great ancestor: He was later deified, with examples such as “Piankhi-yerike-qa” – “Begotten of the deified Piankhi” (Macadam, 1949, p.73). Posterity remembered him well as a holy king who ruled by the will of Amun. He commenced extensive building work at the temple of Amun at Gebel Barkal, and Grimal (1995, p.340) theorizes that to the Kushites, “The Gebel Barkal temple was therefore a replica of the temple of Amun in Karnak” and notes how each king after Piye enlarged upon it, in much the same way had been done at Karnak. Perhaps his work there was a deliberate attempt to start this trend, or was simply an expression of the power and resources that had been given to him by his god. Piye’s stele is certainly not an isolated example of Amun “fundamentalism”, but is a part of a wider context in which Piye can be seen to be attempting to recreate a time of prosperity and devotion to the god that he worshipped. Myśliwiec (2000, p.84) notes “the perfection with which stress is apportioned and appropriate proportions are maintained with regard to its political and religious aspects”, in a “carefully thought-out and didactic manner”. This should demonstrate to us how the stele was a carefully planned way to present Piye in the way that he wanted to be remembered – not as a master political lord, but primarily as a worshipper of Amun. [7]

Shabaka restored the great Egyptian monuments and returned Egypt to a theocratic monarchy by becoming the first priest of Amon. In addition, Shabaka is known for creating a well-preserved example of Memphite theology by inscribing an old religious papyrus into the Shabaka Stone.

Taharqa ruled as Pharaoh from Memphis, but constructed great works throughout the Nile Valley, including works at Jebel Barkal, Kawa, and Karnak.[8] At Karnak, the Sacred Lake structures, the kiosk in the first court, and the colonnades at the temple entrance are all owed to Taharqa and Mentuemhet. Taharqa built the largest pyramid in the Nubian region at Nuri (near El-Kurru).

The Twenty-fifth Dynasty ruled for a little more than one hundred years. The successors of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty settled back in their Nubian homeland, where they established a kingdom at Napata (656–590 BC), then, later, at Meroë (590 BC – 4th century AD).

Kashta

Kashta was an 8th century BC king of the Kushite Dynasty in ancient Nubia and the successor of Alara. His nomen k3š-t3 (transcribed as Kashta, possibly pronounced /kuʔʃi-taʔ/[1]) "of the land of Kush" is often translated directly as "The Kushite".[2] He was succeeded by Piye, who would go on to conquer ancient Egypt and establish the Twenty-Fifth dynasty there.

Piye

Piye (once transliterated as Piankhi; d. 714 BC) was an ancient Kushite king and founder of the Twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt who ruled Egypt from 744–714 BC.[3] He ruled from the city of Napata, located deep in Nubia, modern-day Sudan.

Tantamani

Tantamani (Assyrian UR-daname), Tanutamun or Tanwetamani (Egyptian) or Tementhes (Greek) (d. 653 BC) was a Pharaoh of Egypt and the Kingdom of Kush located in Northern Sudan and a member of the Nubian or Twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt. His prenomen or royal name was Bakare which means "Glorious is the Soul of Re."

Shebitku

Shebitku (also Shabataka or Shebitqo, formerly Shabako) was the second king of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt who ruled from 714 BC-705 BC, according to the most recent academic research. He was a son of Piye, the founder of this dynasty. Shebitku's prenomen or throne name, Djedkare, means "Enduring is the Soul of Re."

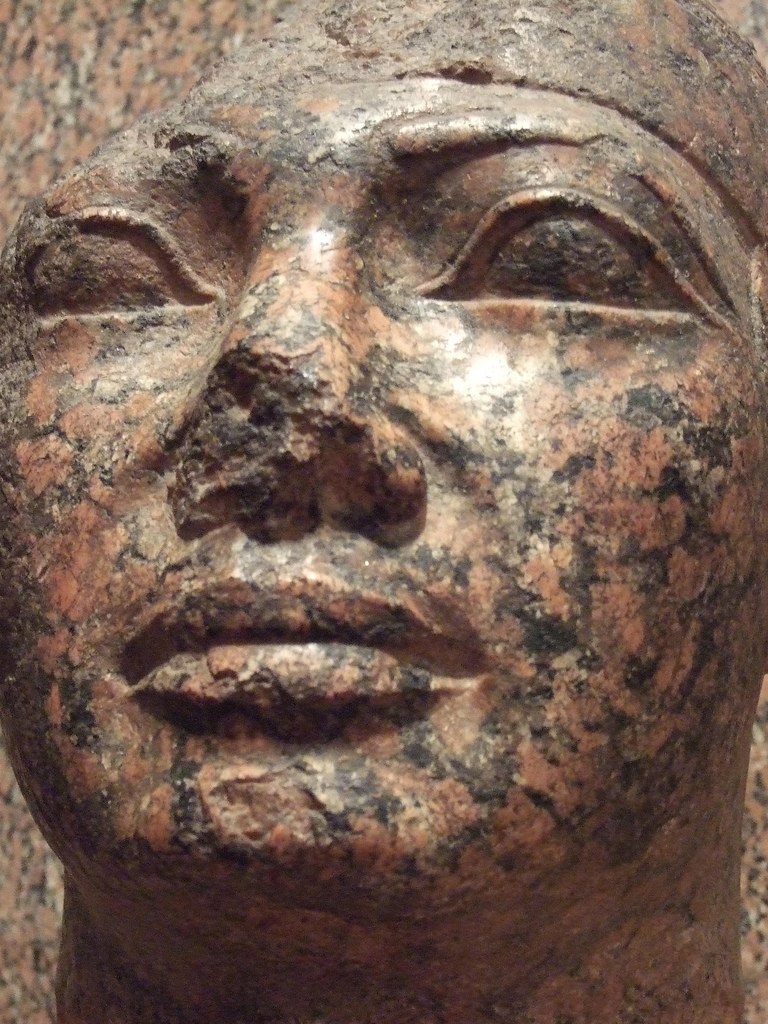

Taharqa

Taharqa, also spelled Taharka or Taharqo (Hebrew: תִּרְהָקָה, Modern: Tirhaqa, Tiberian: Tirehāqā, Manetho's Tarakos, Strabo's Tearco), was a pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt and qore (king) of the Kingdom of Kush (present day Sudan). Although Taharqa's reign was filled with conflict with the Assyrians, it was also a prosperous renaissance period in Egypt and Kush.

Pebatjma

Pebatjma (or Pebatma) was a Nubian queen dated to the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt. She was the wife of King Kashta. She is mentioned on a statue of her daughter Amenirdis I, now in Cairo (42198). She is also mentioned on a doorjamb from Abydos.

Shepenupet II

Shepenupet II (alt. Shepenwepet II, prenomen: Henutneferumut Irietre) was an Ancient Egyptian princess of the 25th Dynasty who served as the high priestess, the Divine Adoratrice of Amun, from around 700 BC to 650 BC. She was the daughter of the first Kushite pharaoh Piye and sister of Piye's successors, Shabaka and Taharqa.

Shabaka

Neferkare Shabaka (or Shabako) was the third Kushite pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt, who reigned from 705–690 BC.

This page uses materials from Wikipedia available in the references. It is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

References