Nubia

Early Period

Early Nubian settlements, begining with the A-Group culture (c. 3800 BC to c. 3100 BC), consisted of "small circular houses with stone foundations, handmade ceramics with elaborate incised decoration, and graves covered with circular stone mounds" [21].

Excavations at Qustul (Lower Nubia) have indicated that the Nubians may have founded the earliest Monarchy in the Nile Valley, dated between 3800 BC to 3400 BC, older than the Scorpion King who was the earliest known Egyptian ruler. [1]

Many features of the A-Group culture were commonly shared with later Nubian settlements, namely the C-Group (2200-1500 BCE) and Pre-Kerma cultures. [21] Archeologists uncovered several ancient constructions dating back to the pre-Kerma period (4th millennium BC- 2600 BC).[3]

The planning of the major Pre-Kerma settlement, in the locality of the Eastern Kerma cemetery, reveals an urban architectural system, where monumental buildings, rectangular storage houses, cattle pens, palisades, and storehouses were uncovered. Exceptionally large huts, with one reaching 7 meters in diameter, found there have been interpreted by some as residence of wealthy individuals.

Moreover, a large number of buildings were found within the expanded town of Kerma... Several buildings have been identified as royal residences; usually consisting of interconnected rooms and courtyard enclosures.

The architectural materials, structures, and the presence of staircases in most of the palaces suggest that they were mostly built of more than one floor. The majority of them had rectangular or square plans with long corridors and narrow rectangular rooms; a hallway was usually present after passing through the main entrance.[3]

Kerma

Kerma (also known as Dukki Gel) was the capital city of the Kerma culture in present-day Sudan. Kerma was settled around 2500 BCE.

It was a walled city containing a religious building, large circular dwelling, a palace, and well laid out roads. [6] Bronze forges were excavated by Bonnet’s Swiss team in the Kerma main city.

It is within the walls of the religious center that a bronze workshop was built. The workshop consisted of multiple forges and the artisans’ techniques appear to have been quite elaborate. There is no comparable discovery in Egypt or in Sudan to help us interpret these remains[9]

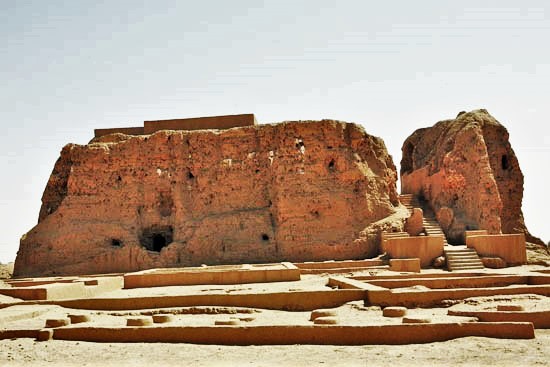

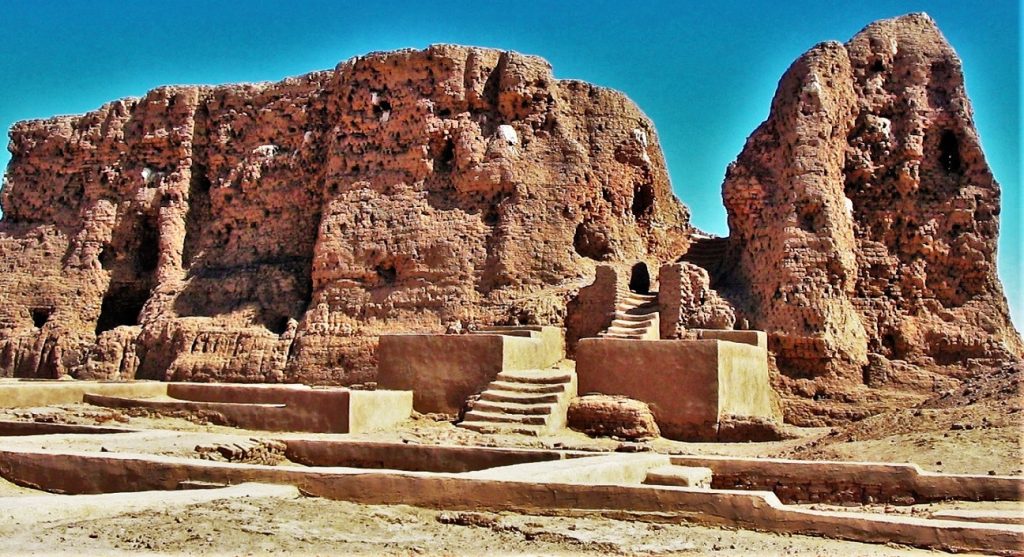

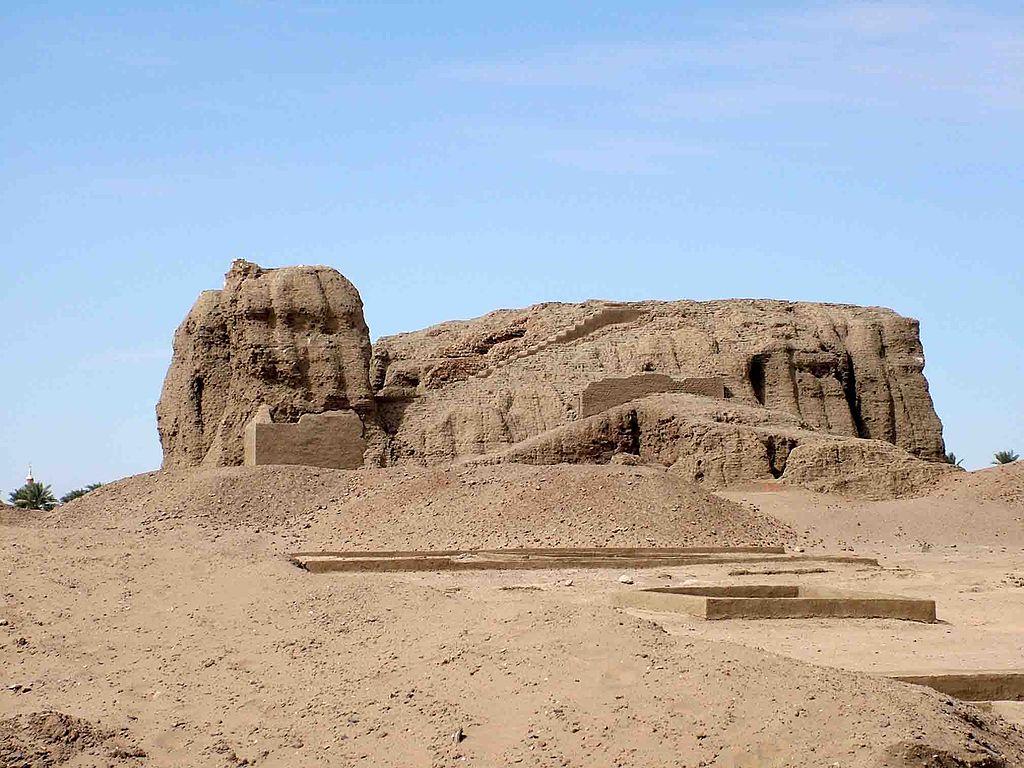

Kerma was built around a large adobe temple known as the Deffufa, a mud brick temple where ceremonies were performed on top.[4]

The deffufa is a unique structure in Nubian Architecture. Three known deffufas exist: the Western Deffufa at Kerma, Eastern Deffufa, and a third, little-known deffufa.

The Western Deffufa forms an imposing sight in the vicinity of the small Sudanese town of Kareema. Like the other Deffufas, it was built of thick mud-brick walls to provide cooler temperature in the hot climate. The structure is comprised of three stories and stretches over an area of 15,070 sq feet and is about 18 m. tall. The Deffufa is farther surrounded by a boundary wall.

Inside the Deffufa were columned chambers connected by a complex network of passageways. The walls were lavishly decorated with faience tiles and inlays and gold leaf. Magnificent paintings showing exotic scenes of the wild-life from the sub-Sahara served as visual luxury in Kerma's arid environment. A staircase seems to have lead to a shrine on the roof of the building. Evidence of a limestone altar, built for animal sacrifice, was also found. The repeated works of construction and development efforts indicate the centrality of the monument in the town of Kerma; most likely the town's principal temple.[7]

The Eastern Deffufa lies 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) east of the Western Deffufa. The Eastern Deffufa is shorter than the Western Deffufa, just two stories high. It is considered a funerary chapel, being surrounded by 30,000 tumuli or graves. It has two columned halls. The walls are decorated with portraiture of animal in color schemes of red, blue, yellow, and black and stone laid floors. Exterior walls were layered with stone.[7]

The third deffufa is of similar structure as the Eastern Deffufa.

Kerma contains a cemetery with over 30,000 graves. The cemetery shows a general pattern of larger graves ringed by smaller ones, suggesting social stratification.

The people of Kerma people buried their dead in niche cut pits. A tumulus or a mound superstructure of sand and gravel, sometimes reaching 90 meters in diameter, was built over the graves of royal persons. The size of the mound indicated the social rank of the deceased person when alive. The larger the tumulus, the higher in rank the owner was; and the smaller it is, the lower in status.

A distinctive element of the Kerma culture was the unique bed burial tradition. The distinctive design and manufacture of the Kerma bed didn't change over time; it represents the traditional Sudanese bed today and is called Angaraib. The deceased was placed on top of the bed. The bed was then placed in the middle of the tomb chamber. On some cases, mummification was conducted on deceased kings and royal persons. The body was usually laid in a contracted body position with the head towards the east.

Flag staffs and square shaped steles were uncovered near tumuli structures and were probably related to the building structures.[8]

Kerma's artefacts are characterized by extensive amounts of blue faience and glazed quartzite[5] which are distinct in details and technique from those in Egypt.

Kush and Napata

Between 1500-1085 BCE, Egyptian conquest and domination of Nubia was achieved. This conquest brought about the Napatan Phase of Nubian history.

In 1075 BCE fragmentation of power in Egypt allowed the Nubians to regain autonomy. They founded the Kingdom of Kush, which was centered at Napata, and eventually conquered Egypt in 750 BC. Their reign was known as the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt.

The reunited Egyptian empire under the 25th dynasty was as large as it had been since the New Kingdom and ushered in a renaissance of Egyptian art and culture. The empire over which they presided was greater in extent than any ever achieved in antiquity along the Nile Valley. [10]

The Nubian Pharaohs, such as Taharqa, built or restored temples and monuments throughout the Nile Valley, including at Jebel Barkal, Memphis, Karnak, Kawa, and elsewhere.

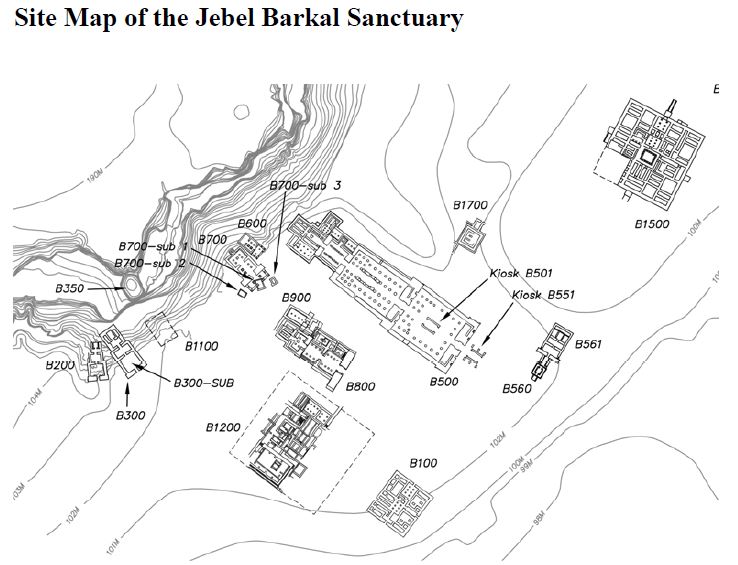

Jebel Barkal was of much spiritual significance to Nubian pharaohs. They held pharaonic coronation and consulted its oracle. It was thought to be the dwelling place of the deity Amun at the Temple of Amun (B500).

The Temple of Amun was originally built during the Egyptian New Kingdom but greatly enhanced by the Nubian King Piye. Piye also constructed the oldest known pyramid at the royal burial site of El-Kurru.

Other temples include Temple of Taharqa (B200); Taharqa's other temples:Temples for Mut, Hathor, and Bes (B300); B501 (outer court), B502 (hypostyle hall), B700 (temple), B800sub (temple of Alara of Nubia), B1200 (palace). In all thirteen temples and three palaces have been excavated by Reisner, labeling its monuments B for Barkal.

At Memphis Shabaka transcribed on a stela known as the Shabaka Stone, an old theological document known as the Memphite Theology, on the deity Ptah, considered the demiurge who existed before all other things and, by his will, thought the world into existence.

At Karnak, several structures are owed to Taharqa including:

- The Kiosk of Tahraqa (690-664 B.C.) originally consisted of ten twenty-one meter high papyrus columns linked by a low screening wall.

-

The Edifice of Taharqa:

He [Taharqa] was interested in Karnak’s “sacred lake” and built the “edifice of the lake” beside it, a partly underground monument.

Today it’s badly damaged although mysterious, “this is a puzzling and enigmatic monument that has no parallels” writes Blyth. “It was “dedicated to Re-Horakhte [a combination of two sky gods], which would explain the open solar court above ground, while the subterranean rooms symbolised the sun’s nocturnal passage through the underworld.” Among its features was a “nilometer” a structure used to measure the water level of the Nile that. In this case, the meter would have had a symbolic use.[11] - Taharqa also added a colonnade to the Precinct of Montu

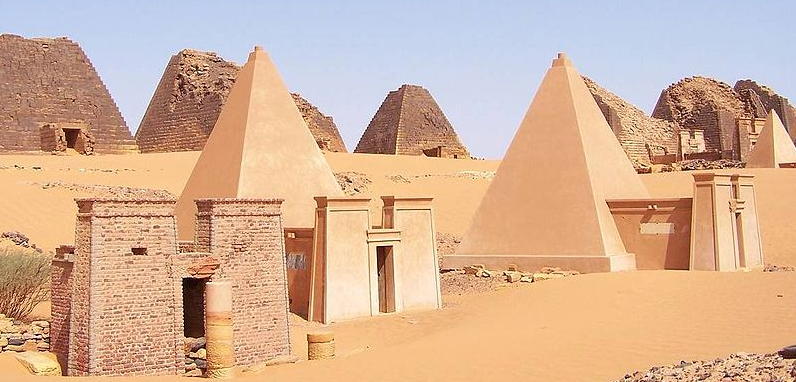

Nubia contains over 220 pyramids, built over a period of hundreds of years, to serve as headstones on top of tombs for Kushite kings, queens and wealthy citizens of Napata and Meroë. They are smaller but greater in number than the pyramids of Egypt.

The general construction of Nubian pyramids consisted of steep walls, a chapel facing East, stairway facing East, and a chamber access via the stairway.[12][13]

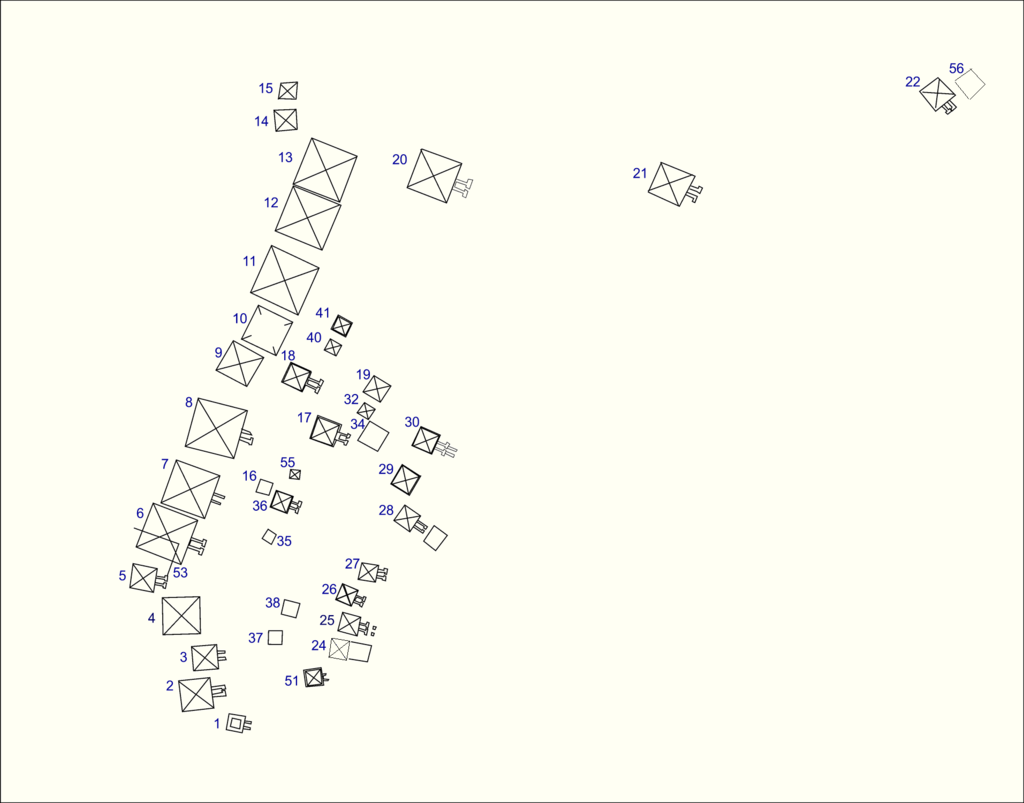

Nubian pyramids were constructed on three major sites: El-Kurru, Nuri, and Meroë.

Meroë

Meroë (c. 785 BC – c. AD 350) was the capital of the Kingdom of Kush.

Meroë is considered to be the largest archaeological site in the world. It contains more Nubian Pyramids than any other site.

The culture shows a mixture of indigenous and Egyptian influences:

Meroitic culture shows much Egyptian influence, always mixed with local ideas. Many temples housed cults to Egyptian gods like Amun (called Amani) and Isis, but indigenous deities received royal patronage as well. A very prominent Nubian god was the lion-deity Apedemak, a god of war whose popularity increased substantially in this period. Local gods were often associated with Egyptian ones: in Lower Nubia, Mandulis, for example, was considered to be Horus's son.

Hybridity is also visible in the arts and in royal ideology. For example, kings of Meroe were represented in monumental images on temples in Egyptian fashion but with local elements, such as garments, crowns, and weapons.[15]

The ancient Nubians established a system of geometry including early versions of sun clocks. Many are located at the sites of Meroë.The ancient Nubians used a trigonometric methodology similar to the Egyptians.[17]

Mapping of standing stones and megalithic structures at Nabta in the Nubian Desert, 500 miles south of Cairo, suggests that the Neolithic nomads who once inhabited the area were not only monitoring the heavens, but recording what they saw in monumental form. According to an article in Nature by J. McKim Malville of the University of Colorado, Fred Wendorf of Southern Methodist University, and others, the megaliths were placed in deposits that probably accumulated between 7,000 and 6,700 years ago in a playa inundated by summer rains.

Alignments of standing stones and megalithic structures (oval clusters of recumbent stones) extend for up to a mile, marking north and east as well as 24 to 28 and 126 degrees east of north, directions whose meanings are still being worked out. A ten-foot circle composed primarily of stone slabs has four "windows" marked by pairs of standing stones; the four are arranged in two pairs, one forming a north-south line of sight and the other a line stretching from 62 to 298 degrees east of north. The latter coincides approximately with the summer solstice sunrise 6,000 years ago, which would have fallen about 63 degrees east of north.

Malville and Wendorf speculate that the megaliths, "partly submerged in the rising waters of the summer monsoon," may have marked the onset of the rainy season and created "a symbolic geometry that integrated death, water, and the sun." They also suggest that the migration of these nomads north as the summer rains dried up about 4,800 years ago may have stimulated the development of complex cultures and degrees of social status in predynastic Upper Egypt. Within a few hundred years, the pharaoh Djoser built the first pyramid, the step monument at Saqqara.[16]

Al-Musawarat Al-Sufra

Al-Musawarat Al-Sufra, is a large Meroitic temple complex in modern Sudan, dating back to the early Meroitic period of the 3rd century BC.[21] It is located in a large basin surrounded by low sandstone hills in the western Butana, 180 km northeast of Khartoum, 20 km north of Naqa and approximately 25 km south-east of the Nile. Its MGRS coordinates: 36QWD3477214671. With Meroë and Naqa it is known as the Island of Meroe, and was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2011.[22] Constructed in sandstone, the main features of the site include:- The Great Enclosure

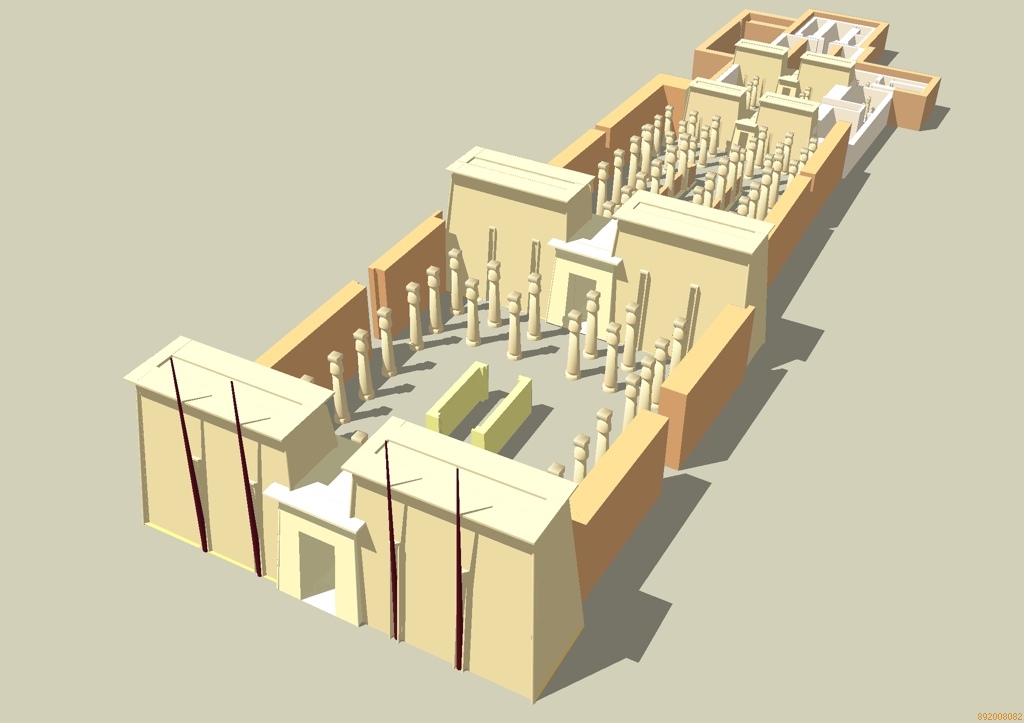

The Great Enclosure is the main structure of the site. Much of the large labyrinth-like building complex, which covers approximately 45,000 m2, was erected in the third century BC.[25] According to Hintze, "the complicated ground plan of this extensive complex of buildings is without parallel in the entire Nile valley".[26] The maze of courtyards includes three (possible) temples, passages, low walls, preventing any contact with the outside world, about 20 columns, ramps and two reservoirs.[27][28]

There were many sculptures of animals, such as elephants and most of the walls of the complex bear graffiti and masons’ or pilgrims' marks both pictorial and in Meroitic or Greek script. [29] The scheme of the site is, so far, without parallel in Nubia and ancient Egypt, and there is some debate about the purpose of the buildings, with earlier suggestions including a college, a hospital, and an elephant-training camp.[23] According to the scholar Basil Davidson, at least four Kushite queens — Amanirenas, Amanishakheto, Nawidemak and Amanitore — probably spent part of their lives in Musawwarat es-Sufra. [30]

- The Lion Temple of Apedemak

- The Great Reservoir

The Great Reservoir is a Hafir to retain as much as possible of the rainfall of the short, wet season. It is 250 m in diameter and excavated 6.3 m into the ground.[31]

Most significant is the number of representations of elephants, suggesting that this animal played an important role at Musawwarat es-Sufra.

Naqa

Naqa or Naga'a is a ruined ancient city of the Kushitic Kingdom of Meroë in modern-day Sudan. The ancient city lies about 170 km (110 mi) north-east of Khartoum, and about 50 km (31 mi) east of the Nile River located at approximately MGRS 36QWC290629877. Here smaller wadis meet the Wadi Awateib coming from the center of the Butana plateau region,[32] and further north at Wad ban Naqa from where it joins the Nile. Naqa was only a camel or donkey's journey from the Nile, and could serve as a trading station on the way to the east; thus it had strategic importance.

Naqa is one of the largest ruined sites in the country and indicates an important ancient city once stood in the location. It was one of the centers of the Kingdom of Meroë, which served as a bridge between the Mediterranean world and Africa. The site has two notable temples, one devoted to Amun and the other to Apedemak which also has a Roman kiosk nearby. With Meroë and Musawwarat es-Sufra it is known as the Island of Meroe, and was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2011.[33]

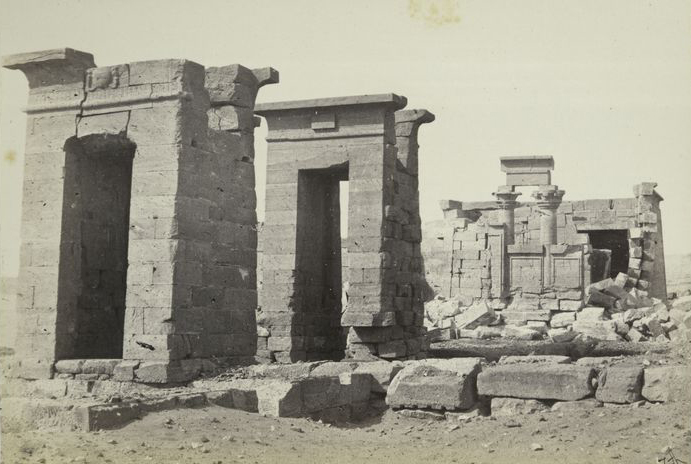

Temple of Amun

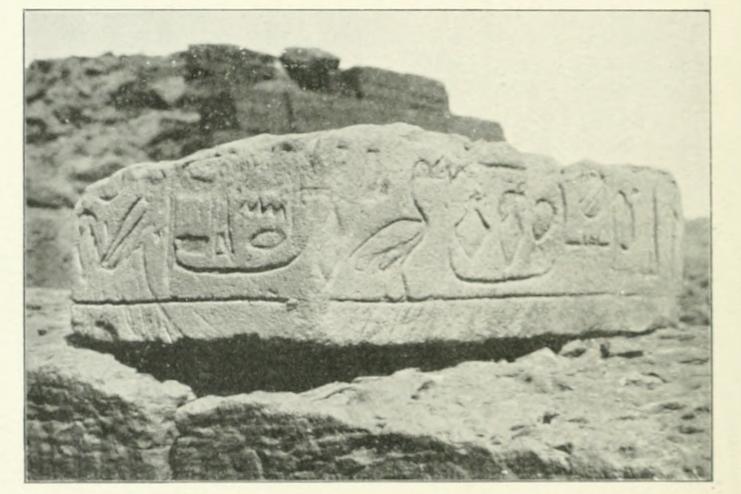

The Amun temple of Naqa was founded by King Natakamani and is 100 metres in length and has several statues of the ruler.[32] The temple is aligned on an east-west axis and is made of sandstone, which has been somewhat eroded by the wind. The temple is designed in the Egyptian style, with an outer court and colonnade of rams similar to the Temple of Amun at Jebel Barkal and Karnak, and leads to a hypostyle hall containing the inner sanctuary (naos).[34] The main entrances and walls of the temple contain relief carvings.

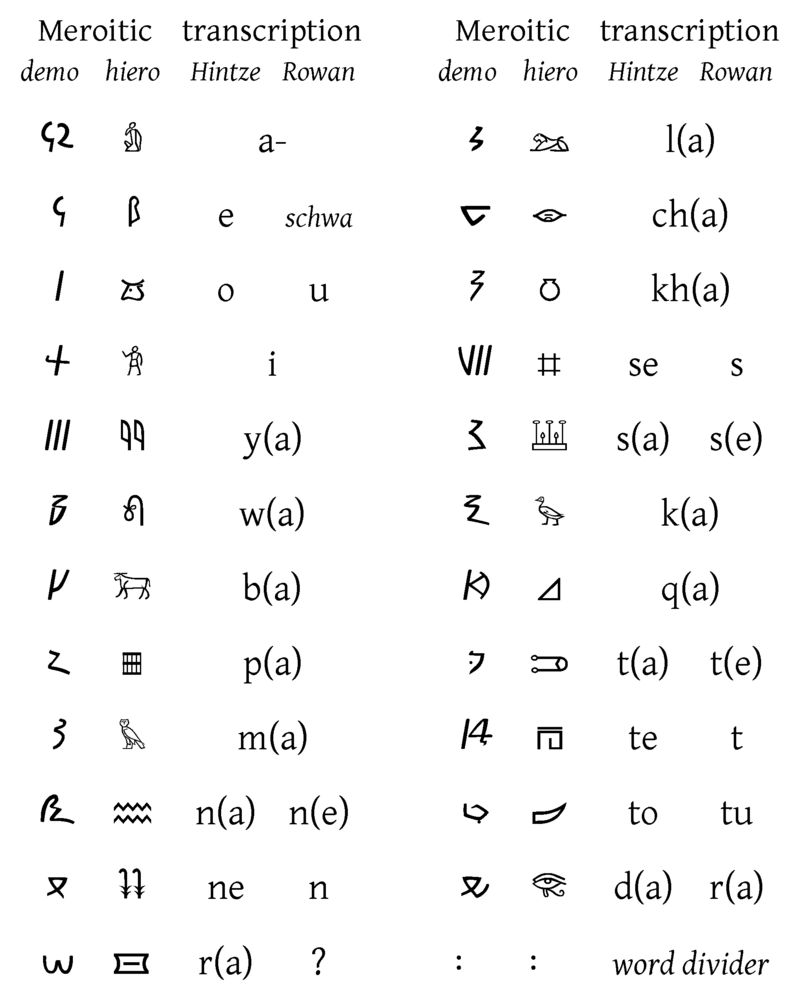

In 1999 the German-Polish archaeology team explored the area of the inner sanctuary of the temple where the main statue of the god was originally kept. They discovered an undamaged painted "altar", which includes iconography and names written in hieroglyphs of the king Natakamani and his wife Amanitore, founders of the temple. The altar is considered unique for Sudan and Egypt in that time period. A fifth statue of the king Natakamani was also discovered in this chamber along with a commemorative stone stela of Queen Amanishakheto who is believed to have been ruling the Meroites prior to the reign of Natakamani and Amanitore. The obverse shows a delicate sunken relief of the queen and a goddess who was a partner of the Meroitic lion god Apademak. The reverse and sides of the stela contain undeciphered Meroitic hieroglyphs and is considered by the discovery team to be one of the best examples of Meroitic art found to date.[32]

Another Amun temple named Naqa 200 and located on the slope of the nearby Gebel Naqa, the mountain overlooking the settlement of Naqa, has been excavated since 2004. It was built by Amanikhareqerem and is similar to the Temple of Natakamani and is dated to the 2nd or 3rd century AD, although some finds do not correspond to the precise dating, adding to an already fuzzy understanding of Nubian chronology.

Temple of Apedemak

Located to the west of the temple of Amun is the temple of Apedemak (or the Lion Temple). Apedemak was a lion-headed warrior god worshipped in Nubia. The god was used as a sacred guardian of the deceased hereditary chief, prince or king. Anyone who touched the chief's grave was said to be cursed by this Apedemak.

The temple is considered a classic example of Kushite architecture. The front of the temple is an extensive gateway, and depicts Natakamani and Amanitore on the left and right exerting divine power over their prisoners, symbolically with lions at their feet. Who the prisoners are exactly is unclear, although historical records have revealed that the Kushites frequently clashed with invading desert clans. Towards the edges are fine representations of Apedemak who is represented by a snake emerging from a lotus flower. On the sides of the temple are depictions of the gods Amun, Horus and Apedemak keeping company in the presence of the king.[34] On the rear wall of the temple is the largest depiction of the lion god, and is illustrated receiving offering from the king and queen. He is depicted as a three-headed god with four arms.[37] The north-front shows the goddesses Isis, Mut, Hathor, Amesemi and Satet. Inside the temple is a carving of the god Serapis who is depicted with Greco-Roman style beard. Another god with a crown is depicted but is unidentified, but believed to be of Persian origin.[34]

Although the architecture of the main Apedemak temple is strongly influenced by Ancient Egyptian architecture, exhibiting some classic Egyptian forms, some of the depictions of the king and queen are fine examples of the differences between Egyptian and Kushite art. King Natakamani and Queen Amanitore are depicted with round heads and broad shoulders, with the relief of Amanitore having unusually wide hips, which is more typical of African art. So the temple of Apedemak illustrates profoundly the fusing together of artistic influences by the Kushites, especially when taking into account the nearby Roman kiosk which clearly is influenced by Ancient Greece and Rome (as discussed below). The depiction of Apedemak displaying a lotus flower is also somewhat unusual, and initially led early archaeologists of Naqa to speculate that the temple had Indian influences, given that trade routes from India led to the ancient Red Sea port of Adulis, in modern-day Eritrea.[34] These connections are still being explored by modern archaeologists.[38]

Christian Nubia

The Christianization of Nubia began in the 6th century AD. Its most representative architecture are churches.

Construction of the churches varried depending on climate of and region:

Cut stone, generally quarried from nearby temples, was the preferred material for the earliest Nubian churches. Roughly dressed native stone, laid in heavy mortar, was also employed. There was some use of mud brick in the smaller churches from the beginning, and in later centuries it became the almost universal building material. Only in the extreme north and the extreme south of Nubia - both areas subject to occasional rainfall - was there some continued use of stone in later times. Red (fired) brick was rarely used except for repairs and secondary construction. Only one church in Lower Nubia, at Faras West, was built primarily of red brick. On the other hand, several churches in Upper Nubia, at Sai, Old Dongola (Church of the Columns), Gandesi, and El Usheir, appear to have been built of red brick.

Many if not all of the earliest churches had flat, timbered roofs which were supported on monolithic columns. However, suitable timber soon became scarce, and in later centuries all Nubian churches had vaulted brick roofs, often with a central dome or cupola. Because of the peculiar unwieldiness of the Nubian vault, this method of construction necessitated in every case the replacement of stone columns by stout masonry piers. The last church in Lower Nubia to be built with columns and (presumably) a flat roof was the South Kom Church at Faras, dedicated in 930 AD...

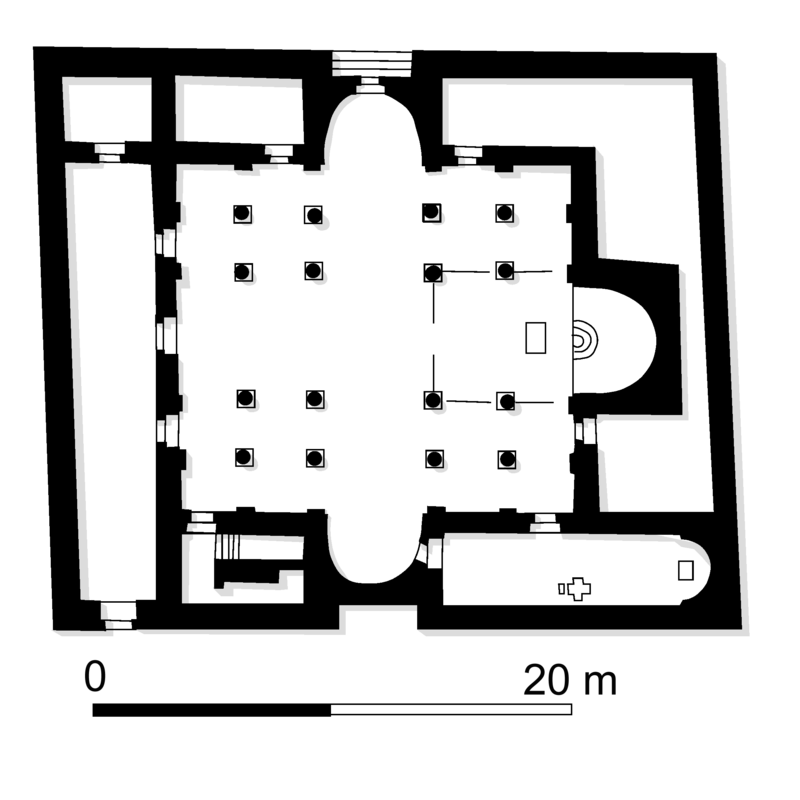

The external plan of the Nubian church is almost invariably a simple rectangle, having its long axis east-west...

Both the overall size of the church building and the proportion of length of width diminished continually during the Christian period. The earliest churches were consistently large, long and narrow. The Basilica at Kasr Ibrim, built probably in the 6th or 7th Century, is the largest known church in Nubia, measuring 3 X 19m. The length width ratio in the early churches averaged 1.67 to 1, and sometimes reached 2 to 1. At the end of the Christian period the dimensions of most churches were under 10m., and the plan was virtually square. The total area covered by the building diminished by 90%, from an average 350sqm. to 35sqm...

The first Nubian churches, whose plan included a narthex, were entered from the west, either by a single door in the center of the west wall or by doors at the extreme western ends of the side (north and south) walls, or both. However, the narthex went out of fashion almost at once, and the mode of entry was altered accordingly. Almost all Nubian churches from the 7th Century onward were entered by doors in the north and the south walls located slightly to the west of the center of the building... [18]

Church painting with biblical themes were extensive but few survived. The best surviving church painting were on the Rivergate Church of Faras and the Church of Ab El Qadir.

One prominent feature of Nubian churches are vaults (dome) made out of mud-bricks. The mud-brick structure was revived by Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy after rediscovering the technique in the Nubian village of Abu al-Riche . The technology is advocated by environmentalist as environmentally friendly and sustainable, since it makes use of pure earth without the need of timber.[19]

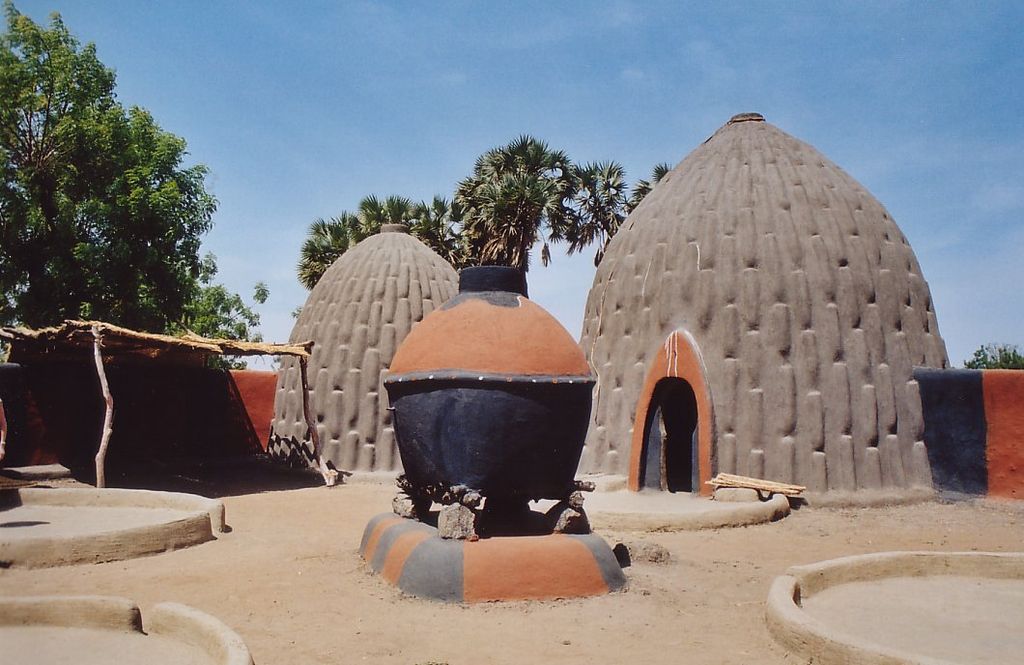

One of the key advantages of the Nubian vault is that it can be built without any support or shuttering. The earth bricks are laid leaning at a slight slope against the gable walls in a length-wise vault, as in this photo of a building from the ruins of Ayn Asil in Egypt. The same principle can be used to build domes, as in the example below from Cameroon.

These environmentally sound, comfortable, and aesthetic buildings require neither imported sheet metal for the roofing, nor expensive and increasingly rare timber beams.

Islamic Nubia

The conversion to Islam was a slow, gradual process, with almost 600 years of resistance. Most of the architecture of the period are mosques built of mud-bricks. One of the first attempt at conquest was by Egyptian-Nubian, Ibn Abi Sarh. Ibn Abi Sarh was a Muslim leader who tried to conquer all Nubia in the 8th century AD. It was almost a complete failure. An agreement called the Baqt, shaped Egyptian-Nubian relations for six centuries, and permitted the construction of a mosque in the Nubian capital of Dongola for Muslim travelers. By the middle of the 14th century, Nubia had been converted to Islam. The royal Church of Dongola was converted into a mosque. Numerous other churches were converted to mosque.[22]

This page uses materials from Wikipedia available in the references. It is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

References