Mandé

Mandé Peoples

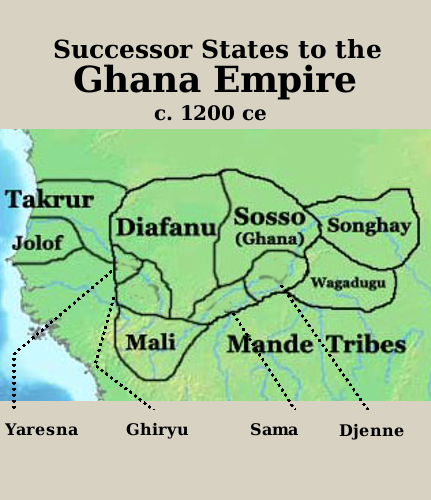

Mandé is a family of ethnic groups in Western Africa who speak any of the many related Mande languages of the region. Various Mandé groups are found in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal and Sierra Leone. The Mandé languages are divided into two primary groups: East Mandé and West Mandé.

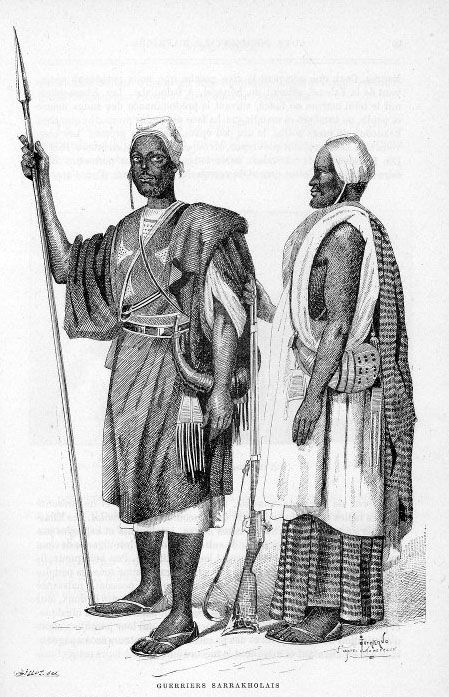

The Mandinka and Malinke people, two western branches of the Mandé, are credited with the founding of the largest ancient west African empires. Other numerous Mandé groups include the Soninke, Susu, Bambara, and Dyula. Smaller groups include the Ligbi, Vai, and Bissa.

Early Period Stone Settlements

The Soninke people were the founders of several stone-base settlements along the sandstone cliffs in the southwestern region of the Sahara Desert, in Mauritania at Dhar Tichitt. One finds well-laid-out streets and fortified compounds, all made out of skilled stone masonry. They are the oldest surviving collection of all stone-base settlement south of the Sahara and are thought to be the precursors of the Ghana empire(c. 750-1240 CE).

The cliffs were settled by agro-pastoral people around 2000–500 BCE. In addition to herding livestock, its inhabitants fished and grew millet. The botanical remains at the site reveal that the pastoralists society practiced some cultivation. Pennisetum or bulrush millet is the only domesticate found at this site, and was most commonly cultivated during the rainy season at upland settlements. During the dry season, wild grains and fruits were collected in the lowlands to supplement the otherwise pastoralist diet.

Dhar Tichitt had become a complex culture by 3600 BP and had architectural and material culture elements that seemed to match the site at Koumbi Saleh with densely packed houses, some more than one storey high, built of stone using banco rather than mortar. In all, there were 500 settlements.

Other settlements were established at the beginning of the thirteenth century along the trans-Saharan trade routes at Oualata, Chinguetti, and Ouadane.

Oualata, a small oasis town in southeast Mauritania, replaced Aoudaghost as the principal southern terminus of the trans-Saharan trade, and developed into an important commercial and religious center. By the fourteenth century the city had become part of the Mali Empire. The old town covers an area of about 600 m by 300 m, some of it now in ruins. The buildings are made of sandstone coated with banco and some are decorated with geometric designs. A mosque now lies on the eastern edge of the town but in earlier times may have been surrounded by other buildings. Today, Oualata is home to a manuscript museum, and is known for its highly decorative vernacular architecture.

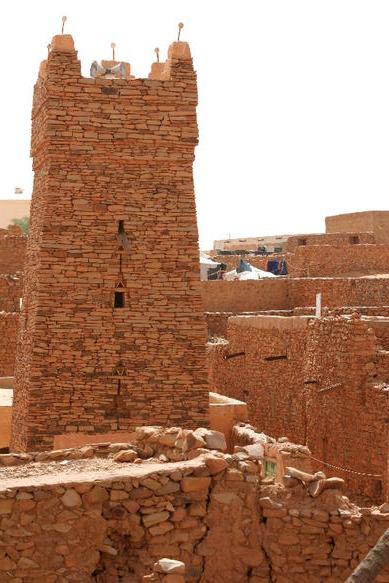

Chinguetti is a Berber medieval trading center in northern Mauritania founded in the 13th century as the center of several trans-Saharan trade routes. The indigenous Berber Saharan architecture of older sectors of the city features houses constructed of reddish dry-stone and mud-brick techniques, with flat roofs timbered from palms. Many of the older houses feature hand-hewn doors cut from massive ancient acacia trees, which have long disappeared from the surrounding area. Many homes include courtyards or patios that crowd along narrow streets leading to the central mosque.

Notable buildings in the town include The Friday Mosque of Chinguetti, an ancient structure of dry-stone construction, featuring a square minaret capped with five ostrich egg finials; the former French Foreign Legion fortress; and a tall watertower. The old quarter of the Chinguetti has five important manuscript libraries of scientific and Qur'anic texts, with many dating from the later Middle Ages.

Ouadane or Wādān is a small town in the desert region of central Mauritania, situated on the southern edge of the Adrar Plateau, 93 km northeast of Chinguetti. The town was a staging post in the trans-Saharan trade and for caravans transporting slabs of salt from the mines at Idjil. A Portuguese trading post was established in 1487, but was probably soon abandoned. The town declined from the sixteenth century and most of it now lies in ruins.

Koumbi Saleh

Koumbi Saleh, sometimes Kumbi Saleh, is the site of a ruined medieval town in south east Mauritania that may have been the capital of the Ghana empire. From the ninth century, Arab authors mention the Ghana Empire in connection with the trans-Saharan gold trade. Al-Bakri who wrote in eleventh century described the capital of Ghana as consisting of two towns 6 miles apart, one inhabited by Muslim merchants and the other by the king of Ghana. The discovery in 1913 of a 17th-century African chronicle that gave the name of the capital as Koumbi led French archaeologists to the ruins at Koumbi Saleh. Excavations at the site have revealed the ruins of a large Muslim town with houses built of stone and a congregational mosque but no inscription to unambiguously identify the site as that of capital of Ghana. Ruins of the king's town described by al-Bakri have not been found. Radiocarbon dating suggests that the site was occupied between the late 9th and 14th centuries.

The houses were constructed from local stone (schist) using banco rather than mortar.[21] From the quantity of debris it is likely that some of the buildings had more than one storey.[22] The rooms were quite narrow, probably due to the absence of large trees to provide long rafters to support the ceilings.[23] The houses were densely packed together and separated by narrow streets. In contrast a wide avenue, up to 12 m in width, ran in an east-west direction across the town. At the western end lay an open site that was probably used as a marketplace.[24] The main mosque was centrally placed on the avenue. It measured approximately 46 m east to west and 23 m north to south. The western end was probably open to the sky. The mihrab faced due east.[25] The upper section of the town covered an area of 700 m by 700 m. To the southwest lay a lower area (500 m by 700 m) that would have been occupied by less permanent structures and the occasional stone building.[26] There were two large cemeteries outside the town suggesting that the site was occupied over an extended period. Radiocarbon dating of charcoal fragments from a house near the mosque have given dates that range between the late 9th and the 14th centuries.[27] The French archaeologist Raymond Mauny estimated that the town would have accommodated between 15,000 and 20,000 inhabitants.[24][28] Mauny himself acknowledged that this is an enormous population for a town in the Sahara with a very limited supply of water ("Chiffre énorme pour une ville saharienne").[24]

Architecture of Mali

Malian architecture developed during the Ghana Empire which founded most of Mali's great cities. They then flourished in West Africa's two greatest civilisations the Mali Empire and the Songhai Empire.

The Mandinka are the descendants of the Mali Empire, which rose to power in the 13th century under the rule of king Sundiata Keita who founded an empire which would go on to span the large part of West Africa. They migrated west from the Niger River in search of better agricultural lands and more opportunities for conquest. The Mandinka people significantly influenced the African heritage of descended peoples now found in the Caribbean, Brazil and the southern United States.

The architecture of Mali is a distinct subset of Sudano-Sahelian architecture indigenous to West Africa. It comprises adobe buildings such as The Great Mosque of Djenne or the University of Timbuktu. This style is characterized by the use of mudbricks and adobe plaster, with large wooden-log support beams that jut out from the wall face for large buildings such as mosques or palaces. These beams also act as scaffolding for reworking, which is done at regular intervals, and involves the local community. Djenné-Djenno is the earliest examples of Sudano-Sahelian style.

Djenné-Djenno

Djenné-Djenno(also Jenne-Jeno) is a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in the Niger River Valley in the country of Mali. The site is known to have been occupied from 250 B.C. to 900 A.D. Literally translated to "ancient Djenné", it is the original site of both Djenné and Mali and is considered to be among the oldest urbanized centers in sub-Saharan Africa. This archaeological site is believed to have been involved in long distance trade and possibly the domestication of African rice. It is also one of the earliest evidence for iron production in sub-Saharan Africa. The city is believed to have been abandoned and moved where the current city is located due to the spread of Islam and the building of the Great Mosque of Djenné.

Great Mosque of Djenné

The Great Mosque of Djenné (French: Grande mosquée de Djenné, Arabic: الجامع الكبير في جينيه) is a large banco or adobe building that is considered by many architects to be one of the greatest achievements of the Sudano-Sahelian architectural style. The mosque is located in the city of Djenné, Mali, on the flood plain of the Bani River. The first mosque on the site was built around the 13th century, but the current structure dates from 1907. As well as being the centre of the community of Djenné, it is one of the most famous landmarks in Africa. Along with the "Old Towns of Djenné" it was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1988.

Timbuktu

The city of Timbuktu has many adobe and mud brick buildings, collectively known as the University of Timbuktu, which were the centres of learning in medieval Mali and produced some of the most famous works in Africa such as the Timbuktu Manuscripts. The most famous of these buildings include the masajids (mosques) of: Sankore, Djinguereber, Kani-Kombole Mosque, and Sidi Yahya.

This page uses materials from Wikipedia available in the references. It is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

References