Abyssinia

Abyssinian People

Abyssinian people (Ge'ez: ሐበሻይት), more commonly known as the Habesha or Abesha (Ge'ez: ሐበሻ, in indigenous texts), is a common term used to refer mainly to the culturally Ethiosemitic-speaking people inhabiting the highlands of Ethiopia or Eritrea. They include a few linguistically, culturally and ancestrally related ethnic groups, conservatively-speaking mostly from the Ethiopian Highlands (but closely related to, if not a subgroup of Cushitic Peoples). Members' cultural, linguistic, and in certain cases, ancestral origins trace back to the Kingdom of Dʿmt and the Kingdom of Aksum.

Abyssinian Architecture varies greatly from region to region. Over the years, it has incorporated various styles and techniques.

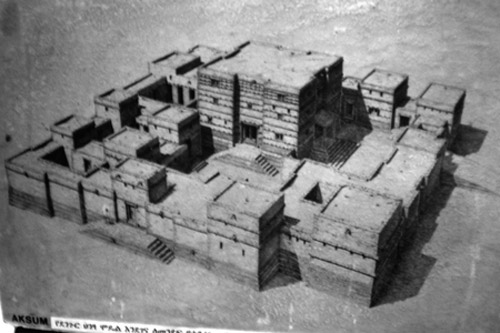

Aksumite Architecture

Throughout the medieval period, the monolithic influences of Aksumite architecture persisted, with its influence felt strongest in the early medieval (Late Aksumite) and Zagwe periods (when the churches of Lalibela were carved). Throughout the medieval period, and especially during the 10th to 12th centuries, churches were hewn out of rock throughout Ethiopia, especially in the northernmost region of Tigray, which was the heart of the Aksumite Empire. However, rock-hewn churches have been found as far south as Adadi Maryam (15th century), about 100 kilometres (62 mi) south of Addis Abeba.

The most famous examples of Ethiopian rock-hewn architecture are the 11 monolithic churches of Lalibela, carved out of the red volcanic tuff found around the town. Although later medieval hagiographies attribute all 11 structures to the eponymous king Lalibela (the town was called Roha and Adefa before his reign), new evidence indicates that they may have been built separately over a period of a few centuries, with only a few of the more recent churches having been built under his reign. Archaeologist and Ethiopisant David Phillipson postulates that Bete Gebriel-Rufa'el was actually built in the very early medieval period, some time between 600 and 800 AD, originally as a fortress but later turned into a church.

Other monumental structures include massive underground tombs, often located beneath stelae. Among the most spectacular survivals are the giant stelae, one of which, now fallen (scholars think that it may have fallen during or immediately after erection), is the single largest monolithic structure ever erected (or attempted to be erected). Other well-known structures employing the use of monoliths include tombs such as the "Tomb of the False Door" and the tombs of Kaleb and Gebre Mesqel in Axum.

Most structures, however, like palaces, villas, commoner's houses, and other churches and monasteries, were built of alternating layers of stone and wood. The protruding wooden support beams in these structures have been named "monkey heads" and are a staple of Aksumite architecture and a mark of Aksumite influence in later structures. Some examples of this style had whitewashed exteriors and/or interiors, such as the medieval 12th-century monastery of Yemrehanna Krestos near Lalibela, built during the Zagwe dynasty in Aksumite style. Contemporary houses were one-room stone structures, or two-storey square houses, or roundhouses of sandstone with basalt foundations. Villas were generally two to four storeys tall and built on sprawling rectangular plans (cf. Dungur ruins). A good example of still-standing Aksumite architecture is the monastery of Debre Damo from the 6th century.

This page uses materials from Wikipedia available in the references. It is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

References