Edo

Edo People

The Edo or Bini (from the word "Benin") people are an ethnic group primarily found in Edo State, and spread across the Delta, Ondo, and Rivers states of Nigeria. They speak the Edo language and are the descendants of the founders of the Benin Empire. They are closely related to other ethnic groups that speak Edoid languages, such as the Esan, the Afemai and the Owan.

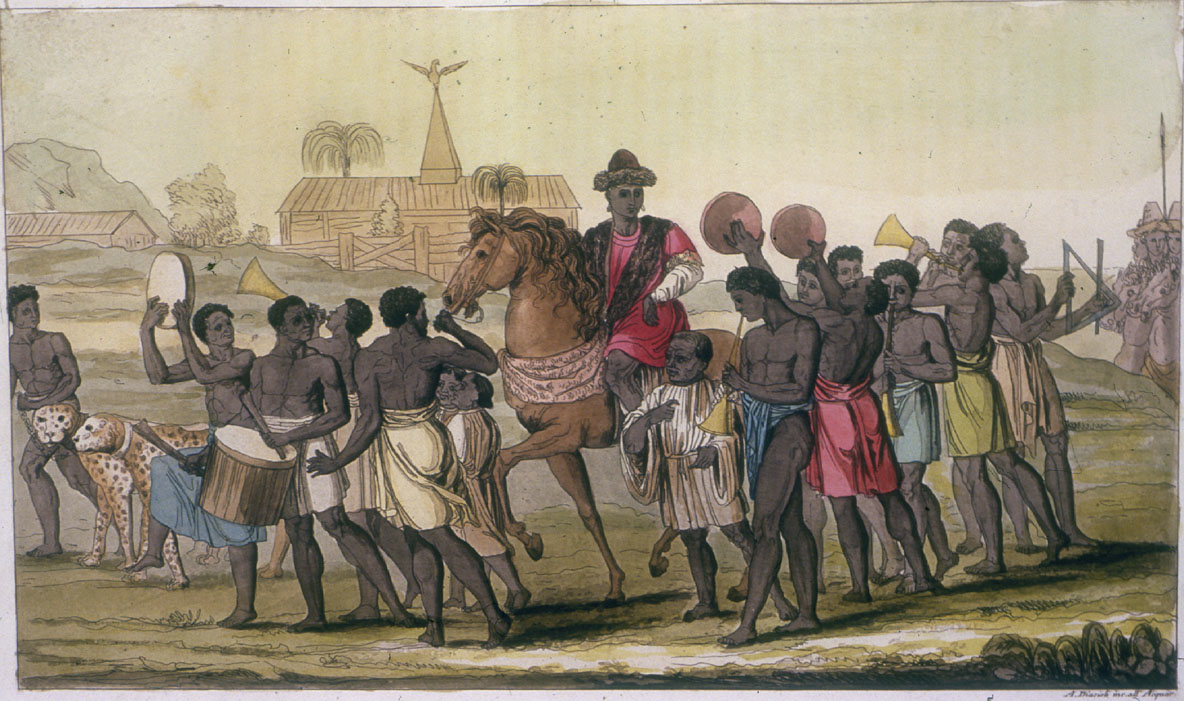

The Oba of Benin is the traditional ruler of the Edo people and all Edoid people and head of the historic Eweka dynasty of the Benin Empire - a West African empire centred on Benin City, in modern-day Nigeria. The ancient Benin homeland (not to be confused with the modern-day and unrelated Republic of Benin, which was then known as Dahomey) has been and continues to be mostly populated by the Edo (also known as the Bini or Benin ethnic group).

The title of Oba was used after the Ogiso title and was created by Oranmiyan, Benin Empire's first "Oba". Oba Eweka I, Oranmiyan's son, is said to have ascended to power at some time between 1280 and 1300. The Oba of Benin was the Head of State (Emperor) of the Benin Empire until the Empire's annexation by the British, in 1897.

Benin City

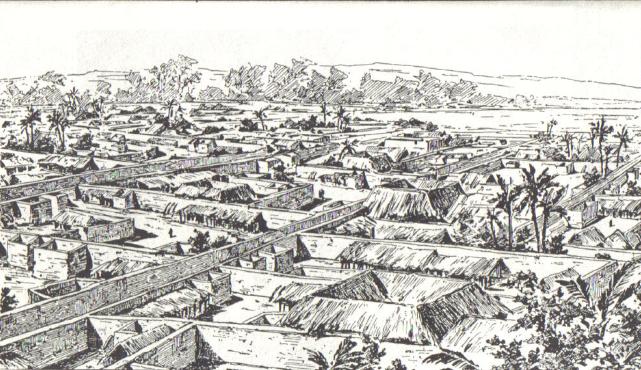

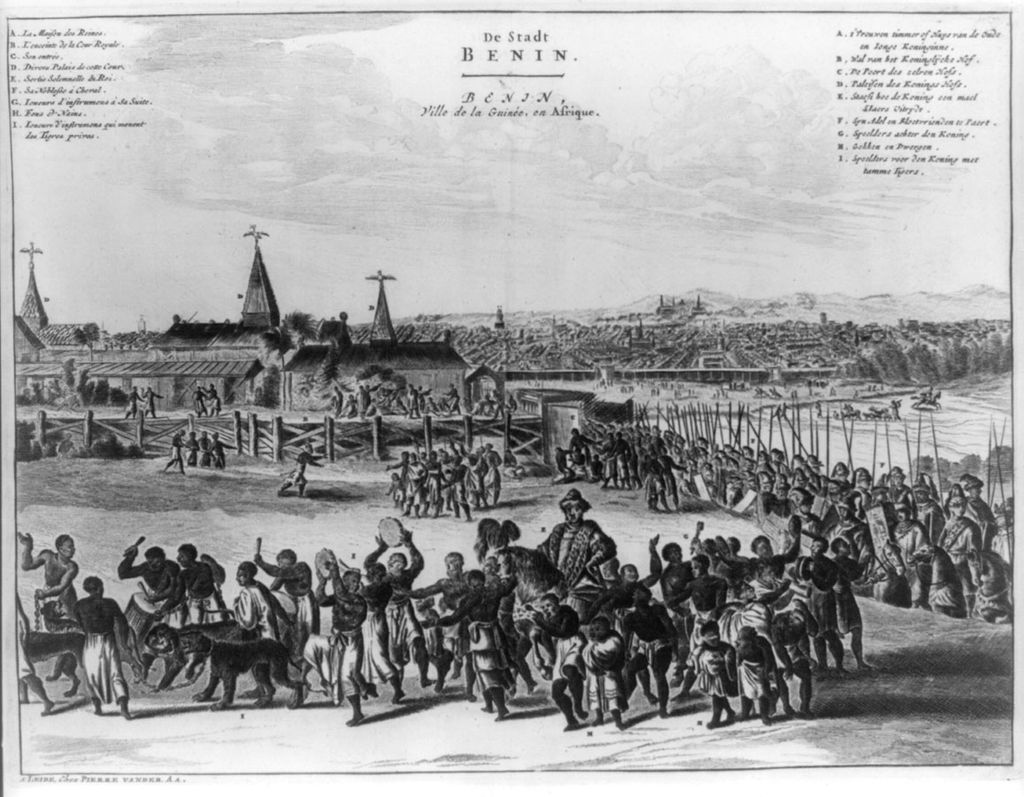

Benin City, originally known as Edo, was once the capital of The Benin Empire. The city was made of hundreds of interlocked cities and villages laid out to form perfect fractals. The main streets had underground drainage made of a sunken impluvium with an outlet to carry away storm water. Metal lamps fuelled by palm oil provided street lighting at night. [4]

The city was designed in a traditional open courtyard house style. The value and relevance of the houses were deteremined by Benin's social, cultural, economic, and political structure. Categories of home ownership, house size, organization and location across the City divided home ownership into hierarchies including commoners, nobles, chiefs, priests, the Oba's palace, and shrines.

The Edo tropicalised architectural pattern was represented by the basic building unit which the Romans called "Atrium" and Edos calls it "Ikun” (Aisien, 2001). The Ikun concept design is a rectangular structure with several open spaces (i.e. Ikuns) surrounded by rooms. Often, family member sit on the corridors under the open space within the Oto-eghodo (Impluvium). The design consisted of several Ikuns strung together in series and each linked to the next by an internal corridor. However, the largest traditional compound in Benin (i.e. oba's palace) has two hundred and one (201) Atria and remains the best existing example of Ikun System of architecture in Benin today (Ekhaese, 2011). The family compounds houses consist of between two to seven Atria (Ikun) this includes the Forecourt Ikun which provides living spaces for male gender, Rear Ikun contained harem for women and children and the side Ikun which provided living spaces for household head. [7]

The traditional Benin courtyard house is an Ikun concept designed rectangular Rampart Earth structure. The sections includes Outer and Inner courts with water collection and drainage system impluvium which drains water underground through the central drain to River.[7]

The height of Benin courtyard house is measured in layers of mud-wattle-wall (a layer is equivalent to 2 regular sandcrete blocks arranged on top of each other). The house height is determined by home owner socio-political status. For instance, Poor/Commoner is 5 layers, Noble is 6 layers, Chiefs/chief priest/diviners is 7 layers, Oba is 7 and above.[7]

The materials for construction are locally sourced and method is through family/community effort. The materials includes; Olila – wood beam, Ere–wood column, Eken n’obar - Rammed-pact earth, Ebeeba - raffia/leaves, Iri – Twine.[7]

In 1691, the Portuguese ship captain Lourenco Pinto observed: “Great Benin, where the king resides, is larger than Lisbon; all the streets run straight and as far as the eye can see. The houses are large, especially that of the king, which is richly decorated and has fine columns. The city is wealthy and industrious. It is so well governed that theft is unknown and the people live in such security that they have no doors to their houses.”[4]

The Edo socio-political structure determined categories of home owners, house size, organization and location across the City.

The oba’s palace complex was the administrative and religious heart of the Kingdom. [6] The earliest known account of the palace was written in the early 1600s by Dutch geographer Olfert Dapper. He described the oba’s palace, based on Dutch travelers reports:

Dapper wrote, “It is divided into many magnificent palaces, houses, and apartments of the courtiers, and comprises beautiful and long square galleries…resting on wooden pillars, from top to bottom covered with cast copper, on which are engraved the pictures of their war exploits and battles.” As Dapper observed, thousands of elaborate brass bas-relief plaques embellished the palace buildings. Today these plaques are an invaluable source for reconstructing and interpreting the kingdom’s hierarchy, history, and rituals. [6]

The palace of the Oba of Benin, Nigeria is very extensive. It is equally as large as a European town, with many courts surrounded by galleried buildings, their pillars encased in bronze plaques. Roofs are shingled with several high towers pinnacle with bronze birds. Everything traditionally takes its root from the Oba’s palace at the city core, from where all broad roads and streets radiate. The Oba palace has a large complex of homes in coursed mud, with hipped roofs of shingles or palm leaves utilizes indigenous traditions Architecture (Ekhaese, 2011).[7]

Walls of Benin

The city of Benin was enclosed by massive walls made from earthworks longer than the Great Wall of China. The Guinness Book of Records (1974 edition) described the walls of Benin City and its surrounding kingdom as the world’s largest earthworks carried out prior to the mechanical era. According to estimates by the New Scientist’s Fred Pearce, Benin City’s walls were at one point “four times longer than the Great Wall of China, and consumed a hundred times more material than the Great Pyramid of Cheops”.[4]

The walls were built of a ditch and dike structure; the ditch dug to form an inner moat with the excavated earth used to form the exterior rampart.

Oba Ewuare, the first Golden Age Oba, is credited with turning Benin City into a city-state from a military fortress built by the Ogisos, protected by moats and walls. It was from this bastion that he launched his military campaigns and began the expansion of the kingdom from the Edo-speaking heartlands.

A series of walls marked the incremental growth of the sacred city from 850 AD until its decline in the 16th century. To enclose his palace he commanded the building of Benin's inner wall, an 11-kilometre-long (7 mi) earthen rampart girded by a moat 6 m (20 ft) deep. This was excavated in the early 1960s by Graham Connah. Connah estimated that its construction if spread out over five dry seasons, would have required a workforce of 1,000 laborers working ten hours a day seven days a week. Ewuare also added great thoroughfares and erected nine fortified gateways.

Excavations also uncovered a rural network of earthen walls 6,000 to 13,000 km (4,000 to 8,000 mi) long that would have taken an estimated 150 million man-hours to build and must have taken hundreds of years to build. These were apparently raised to mark out territories for towns and cities.

The state developed an advanced artistic culture, especially in its famous artifacts of bronze, iron and ivory. These include bronze wall plaques and life-sized bronze heads depicting the Obas of Benin. The most well-known artifact is based on Queen Idia, now best known as the FESTAC Mask after its use in 1977 in the logo of the Nigeria-financed and hosted Second Festival of Black & African Arts and Culture (FESTAC 77).

This page uses materials from Wikipedia available in the references. It is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

References